NTRK和NRG1基因融合在晚期非小细胞肺癌中的作用

前言

基因重排是在实体瘤中发现的最常见的遗传异常之一,具有越来越多的诊断和治疗意义。这些遗传事件最初在血液系统恶性肿瘤中被发现,其中最典型的例子是慢性髓系白血病的断点聚集区/Abelson小鼠白血病病毒癌基因同源重排(BCR-ABL)。然而,在过去的几年里,在各种实体肿瘤中描述了大量的基因重排,部分原因是越来越多的人使用高度先进的测序技术[1]。此外,在合理设计、分子选择的临床试验中实施有效的靶向药物,促使一些药物在仅进行了特定组织学[例如,非小细胞肺癌(NSCLC)[2,3]中的间变性淋巴瘤激酶(ALK)和c-ros原癌基因1(ROS1)重排的克唑替尼]或肿瘤不可知型患者(如神经营养受体酪氨酸激酶中的拉罗替尼和恩曲替尼)的Ⅰ期研究后,迅速获得批准[例如,NSCLC中进行的间变性淋巴瘤激酶(Alk)和c-ros原癌基因1(Ros1)重排的克唑替尼和恩曲替尼]。

在过去的二十年里,肺癌生物学的突破性发现开启了晚期肺癌的新纪元。NSCLC伴随着个性化医疗的兴起而兴起。自2004年发现表皮生长因子受体(EGFR)突变以来,可以从靶向治疗中获益的分子定义的患者亚群列表大幅增加,目前的国际指南建议对所有新诊断为局部晚期或转移性非鳞状NSCLC的患者进行分子检测,寻找5~8个生物标志物,以选择最佳的患者(5~9个)。在NSCLC中发现ALK融合仅4年后,随着新药抑制剂克唑替尼的获批,NSCLC中ALK重排的令人难以置信的故事[10]促使人们寻找其他可能可用于靶向治疗的致癌重排。NeuRegin-1(NRG1)和NTRK融合是最近在NSCLC中发现的两个最新的重排,代表了两个肿瘤不可知性生物标志物的典型例子。虽然相对罕见,但这两种基因异常代表了两个临床上相关的NSCLC亚群,可以从靶向治疗中受益。本文将对NRG1和NTRK重排的NSCLC的生物学和临床病理特征进行全面综述,并提供关于这些靶点的治疗开发的现有数据。

NRG1融合基因

表皮生长因子(EGF)家族在非小细胞肺癌(NSCLC)的癌变和靶向治疗耐药中起重要作用。NRGs是EGF受体的一组生长因子[11]。NRGS家族由4个成员(NRG1、NRG2、NRG3和NRG4)组成,其中NRG1研究最深入。NRG1在神经系统、心脏和乳房的正常生理中起着至关重要的作用,此外在包括癌症在内的一些疾病中也起着病理作用[12]。NRG1有三种主要亚型,即Ⅰ型(Hereglin)、Ⅱ型[胶质生长因子-2(GGF2)]和Ⅲ型[感觉和运动神经元衍生因子(SMDF)],以及6种具有特定功能和表达的次要亚型[13]。

所有的NRGs都是人表皮生长因子受体4(HER4)的配体,而NRG1/2也与HER3结合,并以跨膜分子的形式合成。此外,它们在被去整合素和金属蛋白酶(ADAM)亚家族的膜金属蛋白酶释放后,也可以作为可溶性配体,如肿瘤坏死因子-α转换酶(TACE/ADAM17)。NRGs以自分泌和旁分泌的方式结合,导致HER3的构象改变,二聚化臂可以与其他HER受体,特别是与HER2相互作用,导致细胞内信号级联激活,影响关键的细胞过程,如生长和增殖[14-16]。虽然HER3缺乏显著的酪氨酸激酶活性,但NRGs通过促进与其他HER受体的异二聚化,导致不适当的激活,从而在癌症发生中起重要作用;破坏NRGs与HER3和HER4受体的相互作用可能是一个潜在的治疗靶点(图1)。

除了在癌症发生中起到的作用外,NRGs还与靶向治疗的耐药性有关。Zhou等在对吉非替尼耐药的NSCLC细胞系中观察到,选择性ADAM 17抑制剂(INCB3619)能够逆转对吉非替尼的耐药性,强调了NRG依赖的HER3激活导致非小细胞肺癌对吉非替尼不敏感的原因[17]。NRG1的上调也被认为是NSCLC对ALK抑制剂耐药,以及黑色素瘤的系统治疗和乳腺癌的HER2抑制剂耐药的机制[18,19],NRG1的突变被描述为遗传性疾病,如先天性巨结肠(Hirschsprung Disease)。

截至目前为止,NSCLC已经报道了18个不同的NRG1融合伙伴,尽管这个列表注定会像在其他实体肿瘤中描述的许多其他伙伴基因一样增长[20-22]。CD74-NRG1融合变体是NSCLC中最常见的,由Fernandez-Cuesta等人于2014年首次描述[23]。它由CD74的前6个外显子组成,该外显子与编码NRG1Ⅲ[23]的表皮生长因子样域β的外显子相连。这种基因融合导致NRG1Ⅲ-β3的EGF样结构域在细胞外表达,该结构域与EGF受体相互作用,使HER2-HER3异源二聚化并随后激活。在肺癌细胞系中,CD74-NRG1的异位表达可能通过HER2和HER3受体[23]激活PI3K-AKT通路,从而促进肿瘤细胞的增殖。这种基因融合似乎与2015年世界卫生组织(WHO)肺肿瘤分类[24]中描述的一种罕见的组织亚型特别相关,称为侵袭性粘液腺癌(IMA)[23,25-27],约占所有肺腺癌的5%,在40%~60%的病例[25,28]中存在KRAS突变。IMA与其他常见的肺腺癌亚型(包括皮质型和腺泡型)相比预后较差,很少与EGFR突变和ALK重排相关[25,29,30]。

在对21 858个实体肿瘤样本进行RNA测序分析后,鉴定出41个NRG1融合。CD74-NRG1是最常见的变异(29%),其次是AT1P1-NRG1(10%)和SDC4-NRG1(7%)[20]。其他融合伙伴的发生频率较低,包括NSCLC中的TNC、MDK、DIP2B、KIF13B、RBPMS、MRPL13、ROCK1、DPYSL2、SLC3A2、V Amp2、WRN、ITGB1和PARP8[20-22,25,27,31,32]。正如存在其他癌基因变异的肿瘤中普遍观察到的那样,NRG1融合通常与其他致癌驱动因素相互排斥,如EGFR、BRAF和KRAS突变或ALK、ROS1和RET重排[20]。然而,在某些情况下,NRG1融合可以与其他致癌驱动因素共存,如ALK重排[27,33]和KRAS扩增/突变[27,32,34]。

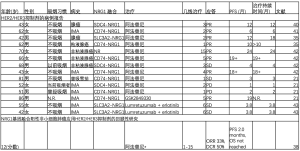

在未选择的NSCLC[35,36]中,NRG1融合的报告发生率为0.2~0.5%(表1)。

Full table

与DNA测序相比,检测NRG1基因融合的金标准是RNA测序,虽然荧光原位杂交(FISH)可以作为其检测的预筛选方法,但只有基因测序才能鉴定基因融合[13]。在最近的117例NRG1阳性肺癌的多中心登记中,基于RNA的检测方法(锚定多重PCR、计数器、RT-PCR和转录组)是最常见的检测方法(79.5%),其次是FISH(12%)和基于DNA的方法(基于杂交捕获的NGS和基于扩增的NGS)(9.4%)[38]。RNA测序对基因重排具有更高的敏感性,与基于DNA的方法相比,RNA测序可以提高对NRG1基因融合的检测,因为基于DNA的方法通常不能覆盖NRG1[21]中的大内含子。

最近对117例NRG1融合阳性的NSCLC进行了一项大型多中心回顾性研究,分析了NRG1融合阳性NSCLC的临床病理特征。NRG1融合与女性(54.7%)、从不吸烟(43.6%)、腺癌组织学(94.9%)、主要为粘液型(71%)和肺转移(Ⅳ期患者为80%)有关。在18例可评价的患者中,以铂为基础的化疗的总有效率(ORR)和疾病控制率(DCR)分别为11%和61%,而PD-1/PD-L1抑制剂单独治疗(n=6)或联合化疗(n=5)(38例)无反应。这些数据虽然受到小样本量的限制,但表明NRG1融合阳性的NSCLC与其他致癌基因成瘾的亚群一致,与免疫检查点抑制剂的低反应性有关,应采取其他治疗策略。

临床前研究表明,NRG1信号通过诱导HER2-HER3异源二聚体,导致随后的PI3K-AKT通路激活并刺激肿瘤生长,而下游信号被HER2/HER3阻断[23,39]所抑制。不同的HER2/HER3抑制剂被批准用于其他临床适应症(如阿法替尼、帕妥珠单抗和来那替尼)或正在积极的临床开发中。一些病例报告和小型回顾性研究提供了这些药物活性的临床证据(表2)。

Full table

阿法替尼是HER家族阻滞剂的一种有效的选择性PAN抑制剂,它与HER家族成员形成的所有同源和异源二聚体[包括EGFR(HER1)、HER2、HER3和HER4]形成的所有同源和异源二聚体共价结合并不可逆转地阻断信号。目前,美国食品和药物管理局(FDA)根据第三阶段试验LUX-RONG-3和-6[44,45]的结果批准其用于治疗EGFR突变的NSCLC,并根据LUXRONG-8研究的结果[46]批准用于治疗先前基于铂的化疗后的鳞状细胞肺癌[46]。越来越多的证据表明,阿法替尼是多种癌症类型(包括非小细胞肺癌)中NRG1融合阳性肿瘤患者的潜在治疗选择,如多个病例报告所述(表2)。最近,一个多中心全球登记117例NRG1阳性病例描述了12例NRG1基因融合的Ⅳ期NSCLC患者中的阿法替尼活性。在这些接受大量预处理的患者(疗程从1到15)中,阿法替尼的ORR为33%,DCR为50%,中位PFS为2.0个月。在少数患者中,观察到了对阿法替尼的长期反应。然而,NRG1基因融合的存在与良好的OS相关(在Ⅳ期患者中为4.83个月),并且不受阿法替尼治疗的显著影响[38]。药物再发现协议试验(DRUP)(NCT02925234)和目标制剂和概况利用注册研究(TAPUR)(NCT02693535)[42]正在进行前瞻性研究。

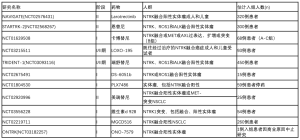

早期临床原则验证数据显示,在晚期NRG1重排癌症患者中,HER3定向靶向治疗是有效的。GSK2849330是一种HER3单克隆抗体(MAb),能阻断NRG1与HER3的结合,抑制受体异构化。Drilon等人。据报道,在一项I期试验(NCT01966445)的NSCLC扩展队列中,一名86岁男性IMA患者携带CD74-NRG1基因融合,对这种HER3单抗有显著的(肿瘤减少32%)和持久的反应(19个月)。这项试验包括了28名HER3表达相似和更高的患者,但没有NRG1基因融合,这些患者中没有一人对治疗有反应。这些临床数据得到了NRG1融合阳性细胞系MDA-MB-175-VII的抗增殖活性和患者来源的异种移植(PDX)小鼠模型中持久的肿瘤消退的临床前证据的支持[21]。相反,与赋形剂相比,阿法替尼显著抑制了肿瘤生长,但在PDX模型中没有观察到肿瘤消退,在3名携带NRG1重排的患者中也没有观察到反应[21]。其他几种HER3抑制剂已经在临床试验中进行了评估,如patritumab(U3-1287,AMG-888),Serbantumab(MM121/SAR256212),lumretuzumab(RG7116),AV-203和elgetomab(LJM 716),这些研究没有集中在NRG1基因融合上。HER2/HER3双特异性抗体MCLA-128可阻断NRG1结合和HER2/HER3异源二聚,在NRG1融合阳性模型中显示出很强的体外和体内活性[47]。全球II期篮子试验(NCT02912949)正在进行中,将在三个NRG1融合阳性队列中评估该化合物的安全性和活性:胰腺癌(n=25)、NSCLC(n=25)和其他实体肿瘤(n=40)。NRG1基因融合检测可以用不同的分子检测方法,如PCR、NGS(RNA或DNA)或FISH[48]。

NTRK融合基因

NTRK基因编码原肌球蛋白受体激酶(Trk)家族蛋白,包括三个成员(TrkA、TrkB和TrkB,分别由NTRK1、NTRK2和NTRK3编码)。这些受体酪氨酸激酶在中枢和外周神经系统发育中起生理学作用,并被不同的配体激活,包括神经生长因子(NGF)、脑源性神经营养因子(BDNF)、神经营养素4(NT-4)和神经营养素3(NT-3)[49-51]。一旦激活,TRK通过三条主要下游通路(MAPK、PI3K和PLC-γ)发出信号,导致神经元发育和分化[52](图2)。

尽管NTRK1、NTRK2或NTRK3基因融合在实体瘤(包括NSCLC)中最常见,但TRK致癌激活的机制可能不同。到目前为止,已经描述了几个基因伙伴,大多数都含有能够组成性激活TRK[51]的激酶结构域的寡聚结构域。

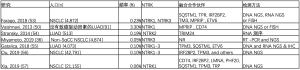

Vaishnavi等人于2013年首次在NSCLC中发现NTRK融合基因。通过对36例无已知致癌改变的肺癌患者的肿瘤样本进行靶向DNA NGS检测,分别鉴定出与MPRIP和CD74融合的两个NTRK1基因。他们还开发了一种FISH检测方法来检测NTRK1重排,在56例未检测到致癌性改变的肺腺癌样本队列中报告了另一例病例(总体频率3.3%)[50]。自初始报告以来,后续研究已在未经选择的患者中发现NTRK融合基因在NSCLC中的频率<1%(表3)。

Full table

与其他致癌性重排(如ALK和ROS1易位)不同,NTRK基因融合与特殊的临床病理学特征相关[58,59],不局限于特定的NSCLC患者亚组且可能同时见于鳞状和非鳞状组织学类型,包括神经内分泌癌,与性别和吸烟状态无关[53]。一项大型回顾性研究分析了166,067例经Foundation Medicine(FMI)测序的真实世界实体瘤样本数据,结果表明NTRK基因融合不与实体瘤中的临床可操作驱动因子共同发生,肿瘤突变负荷(TMB)与NTRK融合阴性实体瘤总体相似,且在亚洲血统患者中的发生频率略高(东亚0.46%、南亚0.37%、美国0.34%、欧洲0.29%和非洲0.32%[60]。此外,NTRK在NSCLC中的基因融合似乎与TMB水平和PD-L1表达频率高于其他分子定义的亚组(EGFR、ALK和ROS1改变的病例)相关,并与STK11突变共存,这与免疫检查点抑制剂的疗效降低相关[61],频率通常与NSCLC相似,但仅低于肺腺癌中的频率[56]。该数据表明NTRK融合阳性NSCLC可能从免疫治疗中获益,而其他癌基因成瘾NSCLC亚组的疗效通常较低[62]。近期在中国人群中进行的一项回顾性研究显示,在既往接受过EGFR酪氨酸激酶抑制剂(TKI)治疗的患者中,NTRK1融合基因可能与EGFR突变基因同时存在,可能代表了这些药物获得性耐药的潜在机制[57]。

除NSCLC外,还在多种肿瘤类型中观察到NTRK融合,可根据以下肿瘤中的融合检出频率进行分组。

- 存在NTRK融合的罕见癌症类型,患病率>90%,包括分泌性乳腺癌、乳腺样分泌癌(MASC)、先天性中胚层肾瘤(细胞或混合亚型)和婴儿纤维肉瘤;

- 常见实体瘤,存在NRTK5-25%的融合,如甲状腺乳头状癌、spitzoid肿瘤、缺乏典型KIT、PDGFRA或RAS的胃肠道间质瘤(GIST)改变,和某些儿童胶质瘤;

- NTRK基因融合发生率低的常见实体肿瘤(<5%,但以<1%为主),如肺癌或胰腺癌、头颈部鳞状细胞癌、胆管癌、乳腺癌、结直肠癌和肾癌、黑色素瘤、成人原发性脑肿瘤(如星形细胞瘤或胶质母细胞瘤)和非GIST软组织肉瘤[51,52]。

到目前为止,已经报道了不同的NTRK融合检测方法,包括免疫组织化学(IHC)、荧光原位杂交(FISH)、逆转录聚合酶链反应(RT-PCR)、基于DNA的NGS、基于RNA的NGS和DNA/RNA杂交测序。每种方法对NTRK融合的灵敏度和特异性不同,周转时间和成本也不同[63]。选择合适的NTRK融合检测方法似乎受到肿瘤类型和相关基因以及其他因素的影响,如可获得的材料、各种临床检测的可及性,以及是否需要同时进行全面的基因组检测。事实上,最近的一项回顾性分析对87例致癌NTRK1-3融合的患者进行了pan-Trk IHC检测,这些患者与基于DNA的靶向NGS(MSK-IMPACT)或基于RNA的测序分析(MSK-Fusion)所确定的各种实体肿瘤有关。与基于RNA的测序相比,基于DNA的测序显示出检测NTRK融合的总体灵敏度和特异度分别为81.1%和99.9%,后者在融合涉及分析未覆盖的断裂点时出现假阴性。IHC的总敏感性为87.9%,特异性为81.1%。不同融合类型的敏感性不同(NTRK1融合为96%,NTRK2融合为100%,NTRK3融合为79%)和不同肿瘤组织学的特异性不同(结肠癌、肺癌、甲状腺癌、胰腺癌和胆道癌为100%,但乳腺癌和唾液腺癌分别为82%和52%)[64]。对于NTRK融合率高(>90%)的罕见肿瘤,如乳腺类似分泌性癌、先天性中胚层肾瘤、婴儿纤维肉瘤或分泌性乳腺癌,FISH或pan-Trk IHC是一种合理的诊断方法。

对pan-Trk IHC阳性病例的NGS确认可与治疗决定同时进行,对FISH/IHC阴性病例应予以考虑。对于NTRK融合频率较低(5-25%)或很少与这些致癌驱动因素相关(<5%)的肿瘤,如肺癌,诊断算法依赖于在常规临床实践中使用NGS作为诊断工具。如果常规进行NGS分子检测,则应将NTRK融合纳入NGS分析。或者,如果没有对特定的肿瘤组织学类型或机构不能进行常规的NGS,可以使用pan-Trk IHC作为筛查试验,然后在阳性病例中进行确认性NGS[65]。同样,欧洲医学肿瘤学会(ESMO)对NTRK检测的建议包括对已知存在高度复发的NTRK融合的实体肿瘤使用FISH、RT-PCR或靶向RNA NGS分析,同时预先使用NGS(最好是基于RNA的),然后IHC确认阳性病例,或者先使用IHC作为筛选工具再使用NGS检测携带低频率NTRK融合的肿瘤(如NSCLC)[66]。

已经开发了几种对TRKA、TRKB和/或TRKC有不同程度活性的TKI,最近美国FDA批准了两种(larotrectinib和entrectinib)。

Larotrectinib(也称为LOXO-101和ARRY-470)是一种高效、高选择性的pan-TRK(TrkA、TrkB和TrkC)ATP竞争性抑制剂,对TRK的抑制选择性比其他激酶高100倍以上,对被测非激酶靶标的选择性>1000倍。此外,Larotrectinib被设计为限制中枢神经系统渗透性,以降低由抑制脑中正常表达的TRK受体引起的潜在神经毒性风险[67]。Larotrectinib治疗NTRK融合阳性肿瘤的开发计划包括三项研究:一项涉及成人的I期研究,一项涉及儿童的I/II期研究,以及一项涉及青少年和成人的Ⅱ期篮子试验(NAVISE)。对登记在Ⅰ期研究中的17种独特的TRK融合阳性肿瘤类型(包括7%的肺癌患者)的前55名患者进行的初步分析报告称,独立中心评审的ORR为75%(每名研究人员80%),DCR为80%。推荐的Ⅱ期剂量(RP2D)为:体表面积≥<1 m2的成人和儿童每日2次,剂量分别为100 mg/m2和100 mg/m2[4]。Larotrectinib耐受性良好,不良事件(AE)主要为1-2级,13%的患者发生3-4级不良事件,只有一名患者因与Larotrectinib相关的不良事件而停用[68]。根据这些初步数据,larotrectinib是第一个获得FDA批准和欧洲医药机构(EMA)有条件批准的同类高选择性pan-TRK抑制剂,与肿瘤组织学无关。

更新该主要队列的数据增加98例,最近在2019年ESMO会议上报告了入组扩展患者队列的患者(共153例)(68例),证实了larotrectinib在NTRK融合阳性患者中的显著活性[79%ORR,95%置信区间(CI):72-85%]。在扩展队列(n=159,包括12例肺癌患者)的综合数据集中,缓解持久,中位缓解持续时间为35.2个月(95%CI:22.8-NE),报告的中位PFS为28.3个月(95%CI:22.1-NE),中位OS为44.4个月(95%CI:36.5-NE)[68]。最近在入组NAVIGATE研究的2例NTRK融合阳性肺腺癌和三阴性乳腺癌患者中报告了larotrectinib的颅内活性[69]。

在初级队列中也报道了有关拉洛替尼耐药机制的初步数据。有趣的是,在6名原发耐药患者中,有1名患者接受了恩替替尼的预处理,并存在NTRK3 G623R突变,这与药物结合的立体干扰有关,5名患者中有3名患者有未经证实的TRK IHC表达。此外,还报道了对larotrectinib获得性耐药机制的初步数据,包括溶剂前沿位置(NTRK1 G595R和NTRK3 G623R突变)或把关位置(NTRK1 F589L突变)或xDFG(激酶激活环的一部分)位置(NTRK1 G667S和NTRK3 G696A突变)的替换[4]。为了克服重复的激酶结构域(溶剂前沿和xDFG)突变介导的获得性抗性,我们设计了一种新一代蛋白激酶抑制剂LOXO-195(BAY 2731954)。这种化合物显示出对所有三种TRK激酶、它们的融合和获得性耐药突变的有效和选择性活性,在临床前和患者中都是如此[70]。最近公布了Ⅰ期研究(NCT03215511,n=20)和FDA扩大准入单患者方案(n=11)的初步安全性和有效性数据。在20例TRK激酶突变患者中,LOXO-195报告的ORR为34%,有希望的ORR为45%(溶剂前沿和xDFG突变均为50%,门卫突变为25%),而在耐药机制不明(17%)和旁路机制(0%)(71例)患者中ORR较低。

在主要队列中也报告了larotrectinib耐药机制的初步数据。有趣的是,在6例原发性耐药患者中,1例接受恩瑞替尼预治疗并携带NTRK3 G623R突变,这与药物结合的空间干扰有关,5例患者中的3例有未证实的TRK IHC表达。此外,还报告了larotrectinib获得性耐药机制的初步数据,包括溶剂前沿位置(NTRK1 G595R和NTRK3 G623R突变)或看门位置(NTRK1 F589L突变)或xDFG(一部分激酶活化环)位置(NTRK1 G667S和NTRK3 G696A突变)置换[4]。为了克服复发性激酶结构域(溶剂前沿和xDFG)突变介导的获得性耐药,设计了新一代TRK抑制剂LOXO-195(BAY 2731954)。该化合物对全部3种TRK激酶及其融合和获得性耐药突变均表现出强效、选择性活性(临床前和患者中)[70]。最近提供了Ⅰ期研究(NCT03215511,n=20)和FDA扩大使用单一患者方案(n=11)的初步安全性和疗效数据。据LOXO-195报告,在20例TRK激酶突变患者中ORR为34%,ORR为45%(溶剂前沿突变和xDFG突变均为50%,看门基因突变为25%),耐药机制不详(17%),存在旁路机制(0%)的患者中ORR较低[71]。

Entrectinib(RXDX-101,NMS-E628)是一种能够穿过血脑屏障(BBB)的pan-TRK、ROS1和ALK ATP竞争性抑制剂[72]。FDA最近批准该药用于治疗NTRK基因融合但无获得性耐药性突变的转移性或无法切除的实体肿瘤患者,以及转移性ROS1阳性非小细胞肺癌的治疗。在119例各种实体瘤患者(包括71例NSCLC[60%])中进行的2项恩瑞替尼Ⅰ期试验(ALKA-372-001和STARTRK-1)的合并分析报告了相对安全的毒性特征,大多数AE为1~2级,仅15%的患者需要降低剂量。RP2D为600 mg/d。报告了初步疗效数据。在没有NTRK13、ROS1或ALK基因重排的患者中,除了1例ALK F124SV突变神经母细胞瘤患者和ROS1/ALK融合阳性患者接受过一个或多个先前的TKI治疗外,没有观察到任何反应。对患有NTRK1-3、ROS1或ALK重排但以前没有TKI的患者(“Ⅱ期合格人群”,n=25)的分析显示,在3名NTRK融合阳性的可测量疾病患者(包括1名NSCLC)中,ORR为100%,另外1名神经胶质瘤患者的OR率为60%。在TKI-naive ROS1(ORR86%)和ALK(ORR57%)重排肿瘤(73例)中也发现了良好的活性。最近在2019年ESMO年会上报告了恩曲替尼I/II期研究(ALKA-372-001、STARTRK-1和STARTRK-2)的最新综合分析[74,75]。在54例NTRK融合阳性实体瘤中,经独立盲法中心复查,恩曲替尼有效率为59.3%,中位有效时间为12.9个月,中位OS为23.9个月(95%可信区间,16.8-NE)。正如预期,即使在基线脑转移患者中,entrectinib也具有高度活性,颅内ORR为54.5%,中位颅内缓解持续时间未达到[75]。NSCLC队列(10名NTRK融合阳性患者)的结果与总体人群的结果一致,ORR为70%,完全缓解为10%(74例)。尽管许多患者出现了深度且具有临床意义的缓解,但最终会对entrectinib产生耐药性。近期使用血浆NGS平台(Foundation Medicine)在入组Ⅱ期篮子试验STARTRK-2的NTRK和ROS1融合阳性患者血浆样本中研究了耐药机制。NTRK和ROS1融合阳性患者中的获得性耐药突变检出率分别为34%和28%,还报告了两组中MAPK通路内获得性耐药的脱靶机制[76]。这些数据与最近使用肿瘤活检和细胞游离DNA评价各种TRK抑制剂耐药机制的报告一致,表明MAPK信号激活是一种复发性和会聚旁路介导的对多种TRK抑制剂的耐药机制,包括第一代(larotrectinib和entrectinib)和下一代(LOXO195)。已证明TRK与MEK抑制剂联合给药可克服上述耐药机制,考虑到毒性不重叠,可能为NTRK融合阳性患者提供一种有前景的治疗策略[77]。

Repotrectinib(TPX-0005)是新一代TRK、ALK和ROS1 TKI,经合理设计可抑制溶剂前线置换(如ALK G1202R、ROS1 G2032R或ROS1 D2033N和TRKA G595R)。

Repotrectinib在体外和体内表现出对各种溶剂前线替代的活性,并在第一次人类剂量递增Ⅰ/Ⅱ期临床试验(Trident-1,NCT03093116)中显示出对晚期ALK、ROS1或NTRK1-3重排癌症患者的初步活性,其中包括一名患有类似乳腺分泌性癌的患者,该患者携带ETV6-NTRK3重排和NTRK3 G623E突变。最初83名患者接受不同剂量的repotrectinib治疗(在禁食/进食条件下从每天40 mg到每天2次200 mg)的初步安全性数据显示出相对安全的毒性情况。大多数AEs是可控的,1~2级。最常见的急诊AEs是头晕(57%)、味觉障碍(51%)、呼吸困难(30%)和疲劳(30%)。发生了4种剂量限制性毒性,并可通过剂量调整加以控制:呼吸困难/缺氧G3(n=1);G2(n=1)和G3(n=1)在160 mg Bid时头晕;G3头晕(n=1)在240 mg,qd时头晕[79]。研究正在进行中,NTRK融合阳性患者的疗效数据值得期待。

在NTRK融合阳性模型中显示临床前活性的其他TRK抑制剂包括新型选择性ROS1/NTRK抑制剂DS-6051b[80]、IGF-1R/NTRK抑制剂BMS-536924[81]、ALK/NTRK双重抑制剂TSR-011[82]、多激酶抑制剂merestinib(LY2801653)[83]和MET/TRK抑制剂阿替尼(DCC-2701)[84]。正在进行的TRK抑制剂治疗NTRK融合阳性实体瘤的临床试验总结见表4。

Full table

结论和未来展望

在分子定义的患者亚组中,对大多数实体瘤(包括NSCLC)具有前所未有的结果。这导致我们对这种疾病的看法发生了巨大的转变,从一种独特的、高频率的、模糊不清的实体的旧概念转变为具有特殊临床-病理和治疗特征的多种不同的分子实体。最近,在不同实体瘤中识别出低频率的罕见基因重排改变了药物开发的旧愿景,导致靶向治疗仅在Ⅰ期研究后获得批准,并独立于肿瘤组织学。NTRK和NRG1基因融合是最令人信服的肿瘤不可知生物标志物的两个例子,尽管在NSCLC中的出现频率非常低,但仍构成了可从匹配靶向药物中获益的两个临床相关患者亚组。TRK抑制剂larotrectinib和entrectinib的批准和下一代TRK TKI的快速临床开发正在重塑该小亚组患者的治疗方案,将NTRK基因融合添加到NSCLC最佳治疗选择应检测的基因列表中。针对NTRK重排的高效和选择性药物的可用性进一步加强了多重分子检测在NSCLC中的实用性,克服了单基因检测的限制。NRG1融合是最新的癌基因驱动因子,已显示出有希望的药理学开发,尽管最佳的治疗序列仍应确定。正在进行的pan-HER TKI(阿法替尼)或靶向HER2/HER3药物的双特异性单克隆抗体(如MCLA-128)临床试验将为该罕见患者亚组的靶向治疗活性提供明确结论。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Alfredo Addeo and Giuseppe Banna) for the Series “Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer” published in Precision Cancer Medicine. The article was sent for external peer review organized by the Guest Editors and the editorial office.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/pcm.2020.03.02). The Series “Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. RM reports grants from Astra Zeneca, other from Genentech, outside the submitted work. SVL reports grants from Alkermes, grants from AstraZeneca, grants from Bayer, grants from Blueprint Medicines, grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, grants from Merck/MSD, grants from Merus, grants from Molecular Partners, grants from Pfizer, grants from Rain Therapeutics, grants from RAPT Therapeutics, grants from Spectrum, grants from Takeda/ARIAD, grants from Turning Point Therapeutics, grants from Ignyta, grants from Clovis Oncology, grants from Debiopharm, grants from Esanex, grants from Genentech/Roche, grants from Eli Lilly, grants from Lycera, grants from Corvus Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Apollomics, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from Celgene, personal fees from G1 Therapeutics, personal fees from Genentech/Roche, personal fees from Guardant Health, personal fees from Janssen, personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees from Loxo Oncology, personal fees from Merck/MSD, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from PharmaMar, personal fees from S.A., personal fees from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Taiho Oncology, personal fees from Takeda/ARIAD, personal fees from Ignyta, personal fees from Tempus, non-financial support from AstraZeneca, non-financial support from Genentech/Roche, non-financial support from Merck/MSD, outside the submitted work. CR reports grants from MSD, grants from Astra Zeneca, grants from ARCHER, grants from Inivata, grants from Merck Serono, grants from Mylan, non-financial support from Oncopass, grants from Lung Cancer Research Foundation-Pfizer, non-financial support from Guardant Health, non-financial support from Biomark inc., outside the submitted work. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosure: Dr. Rolfo reports advisor board role for Inivata, ARCHER, MD Serono, Oncompass (non-financial), and Mylan; speakers’ bureau for Astra Zeneca and MSD; honoraria from Elsevier; grants/research support from Lung Cancer Research Foundation (LCRF), American Cancer Society (ACS), GuardantHealth (non-financial), and Biomarkers (non-financial).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Schram AM, Chang MT, Jonsson P, et al. Fusions in solid tumours: diagnostic strategies, targeted therapy, and acquired resistance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14:735-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1693-703. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaw AT, Ou SHI, Bang YJ, et al. Crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1963-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, et al. Efficacy of Larotrectinib in TRK Fusion-Positive Cancers in Adults and Children. N Engl J Med 2018;378:731-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aggarwal C, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology - Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, version 7.2019. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl_blocks.pdf

- Planchard D, Popat S, Kerr K, et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2019;30:863-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu YL, Planchard D, Lu S, et al. Pan-Asian adapted Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: a CSCO-ESMO initiative endorsed by JSMO, KSMO, MOS, SSO and TOS. Ann Oncol 2019;30:171-210. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalemkerian GP, Narula N, Kennedy EB, et al. Molecular Testing Guideline for the Selection of Patients With Lung Cancer for Treatment With Targeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: American Society of Clinical Oncology Endorsement of the College of American Pathologists/International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/Association for Molecular Pathology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:911-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Aisner DL, et al. Updated Molecular Testing Guideline for the Selection of Lung Cancer Patients for Treatment With Targeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: Guideline From the College of American Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:323-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blackhall F, Cappuzzo F. Crizotinib: from discovery to accelerated development to front-line treatment. Ann Oncol 2016;27:iii35-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gullick WJ. The epidermal growth factor system of ligands and receptors in cancer. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:205-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Falls DL. Neuregulins: functions, forms, and signaling strategies. Exp Cell Res 2003;284:14-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagasaka M, Ou SHI. Neuregulin 1 Fusion-Positive NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:1354-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Montero JC, Rodriguez-Barrueco R, Ocana A, et al. Neuregulins and cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:3237-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jeong H, Kim J, Lee Y, et al. Neuregulin-1 induces cancer stem cell characteristics in breast cancer cell lines. Oncol Rep 2014;32:1218-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Cuesta L, Thomas RK. Molecular Pathways: Targeting NRG1 Fusions in Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:1989-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou B-BS, Peyton M, He B, et al. Targeting ADAM-mediated ligand cleavage to inhibit HER3 and EGFR pathways in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell 2006;10:39-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng H, Terai M, Kageyama K, et al. Paracrine Effect of NRG1 and HGF Drives Resistance to MEK Inhibitors in Metastatic Uveal Melanoma. Cancer Res 2015;75:2737-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kimura M, Endo H, Inoue T, et al. Analysis of ERBB ligand-induced resistance mechanism to crizotinib by primary culture of lung adenocarcinoma with EML4-ALK fusion gene. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:527-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jonna S, Feldman RA, Swensen J, et al. Detection of NRG1 Gene Fusions in Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:4966-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drilon A, Somwar R, Mangatt BP, et al. Response to ERBB3-Directed Targeted Therapy in NRG1-Rearranged Cancers. Cancer Discov 2018;8:686-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pan Y, Zhang Y, Ye T, et al. Detection of Novel NRG1, EGFR, and MET Fusions in Lung Adenocarcinomas in the Chinese Population. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:2003-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Cuesta L, Plenker D, Osada H, et al. CD74-NRG1 fusions in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov 2014;4:415-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, et al. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Genetic, Clinical and Radiologic Advances Since the 2004 Classification. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:1243-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakaoku T, Tsuta K, Ichikawa H, et al. Druggable oncogene fusions in invasive mucinous lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:3087-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gow CH, Wu SG, Chang YL, et al. Multidriver mutation analysis in pulmonary mucinous adenocarcinoma in Taiwan: identification of a rare CD74-NRG1 translocation case. Med Oncol 2014;31:34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shin DH, Lee D, Hong DW, et al. Oncogenic function and clinical implications of SLC3A2-NRG1 fusion in invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung. Oncotarget 2016;7:69450-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maeda Y, Tsuchiya T, Hao H, et al. Kras(G12D) and Nkx2-1 haploinsufficiency induce mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Clin Invest 2012;122:4388-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun F, Wang P, Zheng Y, et al. Diagnosis, clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of pulmonary mucinous adenocarcinoma. Oncol Lett 2018;15:489-94. [PubMed]

- Tsuta K, Kawago M, Inoue E, et al. The utility of the proposed IASLC/ATS/ERS lung adenocarcinoma subtypes for disease prognosis and correlation of driver gene alterations. Lung Cancer 2013;81:371-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dhanasekaran SM, Balbin OA, Chen G, et al. Transcriptome meta-analysis of lung cancer reveals recurrent aberrations in NRG1 and Hippo pathway genes. Nat Commun 2014;5:5893. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xia D, Le LP, Iafrate AJ, et al. KIF13B-NRG1 Gene Fusion and KRAS Amplification in a Case of Natural Progression of Lung Cancer. Int J Surg Pathol 2017;25:238-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muscarella LA, Trombetta D, Fabrizio FP, et al. ALK and NRG1 Fusions Coexist in a Patient with Signet Ring Cell Lung Adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:e161-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trombetta D, Graziano P, Scarpa A, et al. Frequent NRG1 fusions in Caucasian pulmonary mucinous adenocarcinoma predicted by Phospho-ErbB3 expression. Oncotarget 2018;9:9661-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gay ND, Wang Y, Beadling C, et al. Durable Response to Afatinib in Lung Adenocarcinoma Harboring NRG1 Gene Fusions. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:e107-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto S, Matsumoto S, Yoh K, et al. 1481OClinical development of molecular-targeted therapies for non-small cell lung cancer through nationwide genome screening in Japan (LC-SCRUM-Japan). Ann Oncol 2019;30:mdz260.003.

- Duruisseaux M, McLeer-Florin A, Antoine M, et al. NRG1 fusion in a French cohort of invasive mucinous lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Med 2016;5:3579-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duruisseaux M, Liu SV, Han JY, et al. NRG1 fusion-positive lung cancers: Clinicopathologic profile and treatment outcomes from a global multicenter registry. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:9081. [Crossref]

- Shin DH, Jo JY, Han JY. Dual Targeting of ERBB2/ERBB3 for the Treatment of SLC3A2-NRG1-Mediated Lung Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2018;17:2024-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones MR, Lim H, Shen Y, et al. Successful targeting of the NRG1 pathway indicates novel treatment strategy for metastatic cancer. Ann Oncol 2017;28:3092-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheema PK, Doherty M, Tsao MS. A Case of Invasive Mucinous Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma with a CD74-NRG1 Fusion Protein Targeted with Afatinib. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:e200-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu SV, Duruisseaux M, Tolba K, et al. 1969PTargeting NRG1-fusions in multiple tumour types: Afatinib as a novel potential treatment option. Ann Oncol 2019;30:mdz268.096.

- Kim HS, Han JY, Shin DH, et al. EGFR and HER3 signaling blockade in invasive mucinous lung adenocarcinoma harboring an NRG1 fusion. Lung Cancer 2018;124:71-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sequist LV, Yang JCH, Yamamoto N, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3327-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu YL, Zhou C, Hu CP, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (LUX-Lung 6): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:213-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soria JC, Felip E, Cobo M, et al. Afatinib versus erlotinib as second-line treatment of patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the lung (LUX-Lung 8): an open-label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:897-907. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Geuijen CAW, De Nardis C, Maussang D, et al. Unbiased Combinatorial Screening Identifies a Bispecific IgG1 that Potently Inhibits HER3 Signaling via HER2-Guided Ligand Blockade. Cancer Cell 2018;33:922-936.e10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schram AM, Drilon A, Mercade TM, et al. 685TiPA phase II basket study of MCLA-128, a bispecific antibody targeting the HER3 pathway, in NRG1 fusion-positive advanced solid tumours. Ann Oncol 2019;30:mdz247.169.

- Passiglia F, Caparica R, Giovannetti E, et al. The potential of neurotrophic tyrosine kinase (NTRK) inhibitors for treating lung cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2016;25:385-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vaishnavi A, Capelletti M, Le AT, et al. Oncogenic and drug-sensitive NTRK1 rearrangements in lung cancer. Nat Med 2013;19:1469-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cocco E, Scaltriti M, Drilon A. NTRK fusion-positive cancers and TRK inhibitor therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018;15:731-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amatu A, Sartore-Bianchi A, Siena S. NTRK gene fusions as novel targets of cancer therapy across multiple tumour types. ESMO Open 2016;1:e000023. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farago AF, Taylor MS, Doebele RC, et al. Clinicopathologic Features of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring an NTRK Gene Fusion. JCO Precis Oncol 2018;2018.

- Stransky N, Cerami E, Schalm S, et al. The landscape of kinase fusions in cancer. Nat Commun 2014;5:4846. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gatalica Z, Xiu J, Swensen J, et al. Molecular characterization of cancers with NTRK gene fusions. Mod Pathol 2019;32:147-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ou SHI, Sokol ES, Trabucco SE, et al. 1549PNTRK1-3 genomic fusions in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) determined by comprehensive genomic profiling. Ann Oncol 2019;30:mdz260.071.

- Xia H, Xue X, Ding H, et al. Evidence of NTRK1 fusions as resistance mechanism to EGFR TKI in EGFR+ NSCLC. Results from a large-scale survey of NTRK1 fusions in Chinese lung cancer patients. Clin Lung Cancer 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed]

- Russo A, Franchina T, Ricciardi GRR, et al. Central nervous system involvement in ALK-rearranged NSCLC: promising strategies to overcome crizotinib resistance. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2016;16:615-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bergethon K, Shaw AT, Ou SHI, et al. ROS1 rearrangements define a unique molecular class of lung cancers. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:863-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilson TR, Sokol ES, Trabucco SE, et al. 443PDGenomic characteristics and predicted ancestry of NTRK1/2/3 and ROS1 fusion-positive tumours from >165,000 pan-solid tumours. Ann Oncol 2019;30:mdz244.005.

- Skoulidis F, Goldberg ME, Greenawalt DM, et al. STK11/LKB1 Mutations and PD-1 Inhibitor Resistance in KRAS-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov 2018;8:822-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Remon J, Hendriks LE, Cabrera C, et al. Immunotherapy for oncogenic-driven advanced non-small cell lung cancers: Is the time ripe for a change? Cancer Treat Rev 2018;71:47-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solomon JP, Hechtman JF. Detection of NTRK Fusions: Merits and Limitations of Current Diagnostic Platforms. Cancer Res 2019;79:3163-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solomon JP, Linkov I, Rosado A, et al. NTRK fusion detection across multiple assays and 33,997 cases: diagnostic implications and pitfalls. Mod Pathol 2020;33:38-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Penault-Llorca F, Rudzinski ER, Sepulveda AR. Testing algorithm for identification of patients with TRK fusion cancer. J Clin Pathol 2019;72:460-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marchiò C, Scaltriti M, Ladanyi M, et al. ESMO recommendations on the standard methods to detect NTRK fusions in daily practice and clinical research. Ann Oncol 2019;30:1417-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laetsch TW, Hawkins DS. Larotrectinib for the treatment of TRK fusion solid tumors. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2019;19:1-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hyman DM, van Tilburg CM, Albert CM, et al. 445PDDurability of response with larotrectinib in adult and pediatric patients with TRK fusion cancer. Ann Oncol 2019;30:mdz244.007.

- Rosen EY, Schram AM, Young RJ, et al. Larotrectinib Demonstrates CNS Efficacy in TRK Fusion-Positive Solid Tumors. JCO Precision Oncology 2019;1-5. [Crossref]

- Drilon A, Nagasubramanian R, Blake JF, et al. A Next-Generation TRK Kinase Inhibitor Overcomes Acquired Resistance to Prior TRK Kinase Inhibition in Patients with TRK Fusion-Positive Solid Tumors. Cancer Discov 2017;7:963-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hyman D, Kummar S, Farago A, et al. Abstract CT127: Phase I and expanded access experience of LOXO-195 (BAY 2731954), a selective next-generation TRK inhibitor (TRKi). Cancer Res 2019;79:CT127.

- Rolfo C, Ruiz R, Giovannetti E, et al. Entrectinib: a potent new TRK, ROS1, and ALK inhibitor. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2015;24:1493-500. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drilon A, Siena S, Ou SHI, et al. Safety and Antitumor Activity of the Multitargeted Pan-TRK, ROS1, and ALK Inhibitor Entrectinib: Combined Results from Two Phase I Trials (ALKA-372-001 and. Cancer Discov 2017;7:400-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Braud FG, Siena S, Barlesi F, et al. 1488PDEntrectinib in locally advanced/metastatic ROS1 and NTRK fusion-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Updated integrated analysis of STARTRK-2, STARTRK-1 and ALKA-372-001. Ann Oncol 2019;30:mdz260.010.

- Rolfo C, Dziadziuszko R, Doebele RC, et al. 476PUpdated efficacy and safety of entrectinib in patients with NTRK fusion-positive tumors: Integrated analysis of STARTRK-2, STARTRK-1 and ALKA-372-001. Ann Oncol 2019;30:mdz244.038.

- Doebele RC, Dziadziuszko R, Drilon A, et al. LBA28Genomic landscape of entrectinib resistance from ctDNA analysis in STARTRK-2. Ann Oncol 2019;30:mdz394.017.

- Cocco E, Schram AM, Kulick A, et al. Resistance to TRK inhibition mediated by convergent MAPK pathway activation. Nat Med 2019;25:1422-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drilon A, Ou SHI, Cho BC, et al. Repotrectinib (TPX-0005) Is a Next-Generation ROS1/TRK/ALK Inhibitor That Potently Inhibits ROS1/TRK/ALK Solvent- Front Mutations. Cancer Discov 2018;8:1227-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drilon A, Cho BC, Kim DW, et al. 444PDSafety and preliminary clinical activity of repotrectinib in patients with advanced ROS1/TRK fusion-positive solid tumors (TRIDENT-1 study). Ann Oncol 2019;30:mdz244.006.

- Katayama R, Gong B, Togashi N, et al. The new-generation selective ROS1/NTRK inhibitor DS-6051b overcomes crizotinib resistant ROS1-G2032R mutation in preclinical models. Nat Commun 2019;10:3604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chong CR, Bahcall M, Capelletti M, et al. Identification of Existing Drugs That Effectively Target NTRK1 and ROS1 Rearrangements in Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:204-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin CC, Arkenau HT, Lu S, et al. A phase 1, open-label, dose-escalation trial of oral TSR-011 in patients with advanced solid tumours and lymphomas. Br J Cancer 2019;121:131-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- He AR, Cohen RB, Denlinger CS, et al. First-in-Human Phase I Study of Merestinib, an Oral Multikinase Inhibitor, in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Oncologist 2019;24:e930-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olmez I, Zhang Y, Manigat L, et al. Combined c-Met/Trk Inhibition Overcomes Resistance to CDK4/6 Inhibitors in Glioblastoma. Cancer Res 2018;78:4360-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

王琼

中国人民解放军总医院第一医学中心病理科,副主任技师,病理与病理生理学博士,兼任中华生物医学工程杂志、中华病理学杂志等审稿人。参与省部级以上课题3项,获实用新型专利3项,发表多篇SCI、中文文章。(更新时间:2021/9/5)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Russo A, Lopes AR, Scilla K, Mehra R, Adamo V, Oliveira J, Liu SV, Rolfo C. NTRK and NRG1 gene fusions in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Precis Cancer Med 2020;3:14.