非小细胞肺癌的靶向性突变:现状与未来

前言

在过去10年中,非小细胞肺癌(Non-small cell lung cancer,NLCLC)已成为精准肿瘤医学的典型,其基础是发现了越来越多的致癌基因突变,并通过针对性的靶向治疗改善了生存[1,2]。2013年,美国病理学家学院/国际肺癌研究协会/分子病理学协会发布了分子检测指南,当时仅建议应用聚合酶链反应 (Polymerase chain reaction,PCR) 检测表皮生长因子受体(Epidermal growth factor receptor,EGFR;也被称为ERBB1)突变(发生率17%)和应用荧光原位杂交(Fluorescence in situ hybridization)检测间变性淋巴瘤激酶(Anaplastic lymphoma kinase,ALK)融合(发生率7%)[3]。自此,随着基于DNA的商业化第二代测序(Next generation sequencing,NGS)的技术进步,在一个组织样本中已可识别数百个基因变异,并随着多种有效的新型酪氨酸激酶抑制剂(Tyrosine kinase inhibitors,TKI)的快速开发,从而确定了多种可作为治疗靶点的驱动基因突变。包括ROS原癌基因1(ROS proto-oncogene 1,ROS1)融合(2%)、B-Raf原癌基因(B-Raf proto-oncogene,BRAF)突变(2%)、神经营养素受体酪氨酸激酶(Neurotrophin receptor tyrosine kinase,NTRK)融合(1%)、EGFR和人表皮生长因子受体(Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2,HER2,也称为ERBB2)20外显子插入突变(3%)、间质-上皮转换因子(Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition factor, MET)扩增或其14外显子跳跃突变(2%)、转染重排基因(Rearranged during transfection,RET)原癌基因重排(1%)和Kirsten大鼠肉瘤病毒癌基因同源物(Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog,KRAS)突变(25%)。总的来说,已发现超过一半的晚期肺腺癌可能携带有可靶向性的驱动基因突变,从而有希望应用目前批准的和/或研究性的靶向治疗。并且,在不久的将来还可能开发应用其他具有预测作用的基因组学和蛋白质组学的生物标记物[4-6]。越来越多的证据表明,检测这些基因变化的最有效和最经济的方法是应用一个综合性的NGS 组合,而非其他需要更多组织样本和可能需要重复活检的方法[7]。

EGFR

EGFR敏感性突变发生于19外显子(例如:至少三个氨基酸残基的可变性缺失)或21外显子(例如:L858R点突变),从而赋予肿瘤对目前可获及的EGFR TKI的敏感性,如吉非替尼(Gefitinib)、厄洛替尼(Erlotinib)、阿法替尼(Afatinib)、达可替尼(Dacomitinib)和奥希替尼(Osimertinib)。此外,在接受第一代或第二代EGFR TKIs治疗的患者中,约60%会继发20外显子T790M的“把关突变(Gatekeeper mutation)”,导致针对EGFR抑制剂的获得性耐药[8,9]。奥希替尼是第三代共价EGFR TKI,对EGFR突变(包括T790M点突变)具有高度选择性,亦有良好的中枢神经系统(Central nervous system,CNS)渗透性,针对野生型EGFR则相对无效[10]。因此,基于AURA研究的结果,奥希替尼很快获批成为EGFR突变型肺癌的标准二线治疗药物。该研究表明,在T790M耐药突变的患者中,与化疗相比,奥希替尼具有更长的(Progression-free survival,PFS)和更少的不良事件(Adverse events,AE)[10]。在Ⅲ期FLAURA试验中,针对EGFR敏感性突变的患者,比较了奥希替尼与吉非替尼或厄洛替尼用于一线治疗的效果,证明奥希替尼的PFS更优,两组的PFS分别为18.9个月和10.2个月(风险比=0.46;P<0.001)。FLAURA试验的总体生存期(Overall survival,OS)数据尚未正式提交,但根据最近的一份医药新闻稿[11],提示该数据达到了阳性结果。进展后分析表明,接受一线奥希替尼治疗的患者获得了更长的PFS2(定义为二线治疗从随机化到疾病进展的时间),其优于采用二线奥希替尼序贯治疗(先予吉非替尼或厄洛替尼一线治疗),两组的PFS2分别为未达到和20.0个月[12]。总之,这些研究确立了奥希替尼成为EGFR敏感性突变或T790M“把关突变”的患者的标准治疗。值得注意的是,具有罕见EGFR突变(例如:20外显子插入、外显子18 p.E709X和p.G719X、21外显子 p.L861Q)的患者被排除在这些里程碑式的临床试验之外,因此,针对这些罕见EGFR突变患者,无论是化疗、化学免疫治疗,还是靶向治疗,其最佳治疗策略仍在研究中[13-15]。

获得性耐药

奥希替尼的获得性耐药涉及多种机制,甚至可能同时发生,这对寻找奥希替尼耐药后的治疗策略提出了严峻挑战。报道最多的机制包括继发性C797S(7%)或G724S点突变(可改变药物和靶点的结合)、对一系列替代信号通路的依赖增加[包括MET高水平扩增(15%~20%)、HER2扩增(2%)、BRAF和KRAS突变(3%)、PIK3CA突变(7%)等]、或发生小细胞癌组织学转变[16-20]。然而,大多数耐药机制(67%)目前仍不清楚[20]。因此,作为一种策略,将EGFR-TKIs与化疗或血管内皮生长因子(Vascular endothelial growth factor,VEGF)抑制剂联合使用,可能延缓耐药的发生。最近有两项Ⅲ期试验表明,与EGFR-TKI单药治疗相比,第一代EGFR-TKI联合化疗或VEGF抑制剂可改善PFS[21,22]。但不足的是,这两项研究均排除了脑转移患者,并且是在奥希替尼成为一线治疗之前设计的,因此当前的临床实践并未因此而改变。目前,奥希替尼加或不加贝伐单抗的Ⅰ/Ⅱ期试验(NCT02803203),以及奥希替尼加或不加铂/培美曲塞化疗的随机Ⅲ期试验(FLAURA2;NCT04035486),均正在进行中。

由于奥希替尼耐药机制的异质性,目前,在奥希替尼治疗进展后,除了化疗外并没有其他标准治疗,故应鼓励这些患者参与临床试验。建议在奥希替尼治疗进展后再次行组织和/或血液来源的NGS,以确定上述可能存在的耐药突变机制,或了解是否发生小细胞癌转化。例如,ORCHARD临床试验(NCT03944772)采用模块化设计,根据奥希替尼进展后检测到的不同分子生物标记物,形成多个队列[23],且很快将开始招募。也有新的数据表明,当发现特定的次级点突变时(例如C797S反式突变、L718V/Q、G724S),加用第二代不可逆的EGFR抑制剂(如阿法替尼)可能有效,但这并不常见,而且仅在无T790M突变的情况下有效[17,18,24-26]。

另一类有希望的治疗EGFR-TKI耐药的策略是靶向其替代信号通路。例如,在一项Ⅰ期剂量递增研究中,应用EGFR-cMET双特异性抗体(JNJ-372),在部分EGFR-TKI耐药人群中观察到了治疗反应,且其大于或等于3级的不良反应发生率低,这些人群包括18外显子G719A突变、C797S突变、MET扩增和20外显子插入性突变。由于JNJ-372具有抑制EGFR和MET双信号以及启动受体降解和抗体依赖性细胞毒性的能力,所以它可能据此而发挥治疗作用[27]。此外,在正在进行的TATTON和SAVANNAH试验中,针对先前接受EGFR TKI治疗后进展的患者,给予奥希替尼联合选择性MET抑制剂沃利替尼(Savolitinib)治疗。中期结果评估显示,在第一代或第二代EGFR抑制剂治疗后进展的T790M阴性患者队列中,客观缓解率(ORR)为52%,而在使用第三代EGFR抑制剂治疗后进展的患者队列中,ORR为25%[28]。另有一些具有获得性RET融合的病例表明,其对目前正在开发的选择性RET抑制剂有高度反应(见下文RET部分)[29]。一项早期试验还表明,针对23名EGFR耐药患者,结合了拓扑异构酶抑制剂(U3-1402)的HER3靶向抗体-药物复合物显示了其耐受性和抗肿瘤活性[16]。此外,还有其他针对药物结合位点突变的策略,包括正在开发中的别构EGFR抑制剂,该抑制剂可不依赖于激酶ATP位点内的共价相互作用而发挥疗效[30,31]。

病例

一名60余岁无吸烟史的妇女,被发现有其左肺上叶有一5.7 cm的肿块,伴有纵隔淋巴结肿大和恶性胸腔积液。针对其左肺上叶病灶的病理活检提示为肺腺癌,PCR检测提示EGFR突变(19外显子缺失)。予每天口服150 mg厄洛替尼,治疗反应为部分缓解(Partial response,PR)。然后,针对其左上叶残留病灶(2.1 cm)行立体定向放疗作为巩固治疗。继续服用厄洛替尼共22个月后,影像学发现其纵隔淋巴结病灶进展,但无证据表明胸部以外有新的病变。此时施行基于血液的NGS检查,发现EGFR T790M突变(等位基因丰度4.5%)。遂开始服用奥希替尼,经过16个月的治疗后,患者出现隆凸下淋巴结肿大和右肺门淋巴结肿大,提示疾病进展。再次行基于血液的NGS检测,结果提示新出现BRAF V600E突变(等位基因丰度0.4%)伴有T790M克隆丢失,但仍持续显示19外显子缺失(等位基因丰度2.2%)。此时,曾有建议她参加一项针对奥希替尼治疗后进展的临床试验,但因慢性肾病不合格而未能入组。故而,考虑到患者仍持续存在初始的19外显子驱动突变,我们选择继续使用奥希替尼,并加用BRAF/MEK抑制方案,即加用达拉非尼(DaBRAFenib)和曲美替尼(TraMETinib)。通过此三联疗法,她的病情稳定了9个多月,没有出新的病变,此治疗仍在进行中。

该病例说明了几个关键点:(1)BRAF是奥希替尼耐药的EGFR突变肿瘤克隆的潜在旁路信号通路[32];(2)在肺癌,BRAF V600E是一种可靶向的驱动突变,可通过达拉非尼联合曲美替尼进行有效的靶向治疗;(3)在同时具有BRAF和EGFR敏感突变的情况下,奥希替尼、达布拉非尼和曲美替尼的三联治疗是一种可耐受的方案[33,34];(4)针对致癌基因驱动的肺癌,在疾病进展时进行NGS检测,可以获得相应信息。值得注意的是,在EGFR突变肺癌进展时,应进行再次组织活检,以评估是否存在小细胞转化。然而,在本例患者,我们通过液体活检发现了一条旁路信号通路(BRAF V600E),该旁路提示存在此类耐药机制,因此取消了组织活检计划。

ALK

一线

肺腺癌中ALK的组成性激活是由染色体重排引起的,该重排产生融合蛋白,最常发生于棘皮动物微管相关蛋白4(Echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4,EML4)和ALK之间,从而通过与下游JAK/STAT、PI3K/AKT和MEK/ERK信号通路的相互作用而导致细胞增殖和侵袭[35]。目前,已上市五种高活性ALK-TKI,即克唑替尼(Crizotinib)、赛瑞替尼(Ceritinib)、阿来替尼(Alectinib)、布加替尼(Brigatinib)和劳拉替尼(Lorlatinib),还有其他几种还在临床研究中。在PFS和ORR方面,克唑替尼是第一个在初治患者中显示出优于化疗的ALK抑制剂,然而,颅内复发通常在治疗后12个月内发生[36]。赛瑞替尼属于第二代ALK-TKI,与克唑替尼的区别在于,针对获得性克唑替尼耐药突变(例如Leu1196MET、Gly1269Ala、Ile1171Thr和Ser1206Thr),赛瑞替尼仍有活性,而且针对CNS病灶效果更好。在赛瑞替尼的临床试验中,发现其常见的不良事件为胃肠道毒性,但是,予每天较低的剂量(450 mg),并且与食物一起服用,则可改善这一情况[37]。自2017年ALEX试验发表以来,阿来替尼因其更好的疗效、更轻的不良事件、对克唑替尼耐药突变仍有疗效、以及出色的中枢神经系统渗透性而成为治疗ALK驱动型肺癌的标准一线疗法[38,39]。根据ALTA-1L试验(该试验比较了布加替尼和克唑替尼)的结果,第二代ALK抑制剂布加替尼于2018年成为初治的ALK重排非小细胞肺癌患者的另一种非标签选择[40]。不幸的是,在第二代ALK-TKIs(如阿来替尼、布加替尼、赛瑞替尼)之间,并没有直接相互比较的数据,治疗的选择取决于药物的可及性、不良事件特征以及对全身和中枢神经系统的活性。此外,在未来几年内,预计将有两项另外的临床试验的结果呈现:在未应用过ALK抑制剂的患者中,比较恩沙替尼(Ensartinib)与克唑替尼的疗效,以及比较劳拉替尼与克唑替尼的疗效。目前,劳拉替尼在美国尚未获得批准作为一线治疗应用。

复发

无论初始治疗如何,所有患者最终都会产生治疗耐药和临床进展。与克唑替尼(20%~30%)治疗后相比,在使用第二代ALK抑制剂(>50%)治疗后,ALK结构域内的耐药突变更为常见[35,41]。并且,在使用第一代、第二代和第三代ALK抑制剂进行序贯治疗后,约12.5%的患者会产生复合性ALK突变(同一等位基因上不止一个突变)[41,42]。使用第二代ALK-TKIs治疗后最常见的耐药突变是G1202R的Solvent-front区域的突变,据估计,这种突变发生于20%的应用赛瑞替尼的患者,30%的应用阿来替尼的患者,和40%的应用布加替尼的患者[41]。重要的是,已发现了多种EML4-ALK变异体,并且对于大多数获得性耐药突变而言,劳拉替尼似乎是最有效的ALK抑制剂[43]。在G1202R突变的患者中,劳拉替尼的ORR为57%,中位PFS为8.2个月[43]。此外,劳拉替尼具有良好的颅内活性,ORR高达87%[44]。最后,为了明确最佳治疗顺序并确定最常见的ALK耐药突变的最有效治疗,国家癌症研究所设计了ALK Master Protocol(NCT03737994),该方案将对具有G1202、C1156Y、I1171、L1196、V1180、F1174或复合突变的患者进行分配,分别应用劳拉替尼、赛瑞替尼、阿来替尼、布加替尼、恩沙替尼、克唑替尼或化疗来进行治疗。

ROS1

与ALK融合阳性NSCLC相比,ROS1重排往往发生于更年轻的患者群体,罕见或无吸烟史,具有更低的脑转移发生率[45,46]。ROS1和ALK在ATP结合位点内具有大量的氨基酸序列同源性,因此许多ALK-TKI在ROS1重排肺癌中具有活性(阿来替尼除外)。克唑替尼是研究最充分的ALK/ROS1抑制剂,针对先前接受过一种或多种化疗的ROS1重排的非小细胞肺癌患者,克唑替尼的ORR为72%,中位PFS为19.3个月,反应持续时间(Duration of response,DOR)为24.7个月[47,48]。该队列的4年生存率为51%,所以食品和药物管理局(Food and Drug Administration,FDA)批准克唑替尼用于ROS1阳性NSCLC[47]。针对初治患者,其他处于早期研究的TKI包括赛瑞替尼和NTRK/ROS1抑制剂恩曲替尼(Entrectinib)。使用赛瑞替尼的单臂试验显示,ORR为62%,中位PFS为19.3个月,这与使用克唑替尼的结果相似[49]。然而,根据ALK阳性患者的数据以及在赛瑞替尼/ROS1试验中8名患者中有5名患者出现反应,相比克唑替尼,赛瑞替尼可能具有更强的CNS活性[49]。最近,根据对三项单臂试验(ALKA、STARTRK-1、STARTRK-2)的分析,FDA批准恩曲替尼用于ROS1和NTRK阳性患者。共纳入51例ROS1阳性的非小细胞肺癌患者,ORR为78%,且在55%的患者的DOR至少持续12个月[50]。恩曲替尼具有良好的中枢神经系统渗透性,初步结果显示颅内ORR为55%,中位PFS为13.6个月[45,51]

大多数肿瘤学指南建议将克唑替尼作为初始治疗(尽管在恩曲替尼获得FDA批准后可能会发生变化),但它不可避免地会产生耐药性。G2032R(类似于solvent front 类型的ALK G1202R耐药突变)已被确定为ROS1结构域内最常见的耐药突变,发生在约41%的病例[52,53]。克唑替尼治疗后的数据相对较少,然而,第一项关于劳拉替尼的人体研究同时招募了ALK和ROS1阳性患者。在其中一个ROS1扩展队列中,纳入了34/47名先前接受过克唑替尼治疗的患者,在中位PFS为8.5个月的患者中,有26.5%的患者出现客观反应[54]。此外,4例G2032R耐药突变的患者在劳拉替尼治疗下维持了长达9.6个月的病情稳定(Stable disease,SD)状态,有3例不同ROS1突变的患者治疗达到了PR的效果[53]。这些数据表明,针对克唑替尼或其他ROS1-TKI治疗后进展的患者,劳拉替尼仍具有一定的活性。另一种有前景的药物是下一代ROS1/TRK/ALK抑制剂——洛普替尼(Repotrectinib),该药物专为克服solvent front类型的G2032R耐药突变而设计。尽管研究队列较小(n=11),但在TRIDENT-1研究中,洛普替尼作用于未应用过ROS1 TKI的患者,ORR为82%(9/11名患者),CNS反应为100%(3/3名患者)。相对应地,在之前接受过一种或多种ROS1靶向治疗的患者中,洛普替尼达到的ORR为39%(7/18名患者),临床受益率为78%(14/18名患者)。CNS反应为75%(3/4患者)。值得注意的是,对于之前接受过ROS1靶向治疗的患者,高剂量的洛普替尼可能更为有效。头晕和味觉障碍是最常见的不良反应,被认为是TRK抑制的一种类效应。该研究的第二阶段将于今年晚些时候开始招募。

BRAF

在肺癌,导致下游MAPK通路组成性激活的BRAF变异是一种新的驱动突变,亦是癌基因驱动的肺癌发生靶向治疗获得性耐药的机制之一[34]。BRAF融合虽然罕见(约占NSCLC BRAF变异的4%),但在EGFR-TKI治疗后进展的患者中,BRAF融合往往作为一种下游替代信号通路而出现[32]。肺癌中,大约一半的BRAF突变是由于第15外显子中V600E氨基酸替换所引起,这在非吸烟者患者中更为常见,但也可能发生在有吸烟史的患者中[55],这种情况可作为BRAF-MEK抑制剂的有效靶点。这方面研究最充分的治疗组合是达拉非尼联合曲美替尼,当作为一线治疗时,ORR为64%,中位PFS为10.9个月,中位OS为24.6个月[56]。当达拉非尼联合曲美替尼作为后线治疗时,研究者评估的有效率为67%,中位PFS为10.2个月,中位OS为18.2个月,结果与一线治疗时相似[57,58]。在这些试验中,纳入中枢神经系统转移的患者数量有限,但根据转移性黑色素瘤的数据,达拉非尼和曲美替尼确实表现出颅内活性[59]。作为一线治疗,由于没有将达拉非尼和曲美替尼与化疗或化学免疫治疗进行比较的随机数据,所以,大多数肿瘤学指南指出,靶向治疗或化疗是均是合理的初始治疗可选方案。

免疫治疗在BRAF突变肺癌中的作用存在争议,因为从历史上看,与缺乏驱动突变的患者相比,癌基因驱动的肺癌患者对免疫治疗的应答率较低,生存结局较差[60]。然而,国际多中心的“免疫靶向”(IMMUNOTARGET)注册研究中,针对BRAF突变患者的回顾性亚组分析表明,PD-1/L1抑制剂可能对有吸烟史的BRAF突变患者或非V600E突变患者有效[60]。此外,Ⅱ类(非V600激酶激活二聚体)和Ⅲ类(非V600激酶失活异二聚体)BRAF突变仅发生在有吸烟史的患者中,并且与脑转移的发生有关[61]。这些数据表明BRAF突变型NSCLC是一类异质性疾病,某些亚型可能受益于化学免疫治疗[62]。

一个活跃的研究领域是针对非V600E突变以及对达拉非尼和曲美替尼产生耐药的V600E突变患者开发治疗方法。传统上,这些患者接受二线化疗,但目前有几种新药正在进行早期临床试验,如第三代RAF抑制剂、泛RAF抑制剂(例如LY3009120、TAK-580、PLX8394、LXH254)和选择性ERK抑制剂(例如Ulixertinib、乌利替尼)。选择性ERK抑制剂有希望具有拮抗BRAF剪接变异体、扩增和次级突变(导致下游BRAF非依赖性ERK信号传导)的活性[32,63,64]。

NTRK

NTRK基因通常编码TRK蛋白,TRK蛋白参与神经营养素结合并激活下游MAPK、PI3K、蛋白激酶C和其他SHC-非依赖性信号通路(通常参与神经元发育和存活)[65]。已有数种NTRK变异被报道,包括突变、剪接变体和TRK过表达,但到目前为止,最常见的致癌NTRK改变是涉及转录因子(如EML4、ETV6)和NTRK1、NTRK2或NTRK3基因的基因融合。这些融合发生在<1%的NSCLC中,但也可作为其他常见肿瘤(如头颈癌、乳腺癌、胃肠道癌、黑色素瘤、原发性脑肿瘤)的罕见驱动突变发生,或作为某些罕见肿瘤(如分泌性乳腺癌、乳腺类似物分泌性癌、婴儿纤维肉瘤等)的特殊病症改变。通常情况下,应用基于DNA的NGS组合来诊断NTRK融合。然而,由于这些基因中存在大量非编码区,因此,尤其是NTRK2和NTRK3融合可能更难通过基于DNA的NGS来检测;因此,通过额外的基于RNA的测序,可以改善诊断的敏感性[65,66]。

拉罗替尼(Larotrectinib)是研究最充分的选择性TRK抑制剂,FDA批准用于任何具有NTRK基因融合且无已知获得性耐药突变的实体瘤。在一项包括儿童和成人NTRK融合患者的三个Ⅰ/Ⅱ期临床试验(组织类型不可知)的汇总分析中,在成人队列,发现有75%的患者有明确的应答,中位PFS为25.8个月[67,68]。虽然只有7例原发性肺癌患者被纳入这项分析,但7例中有3例达到完全缓解(Complete response,CR),有2例达到PR,有2例达到SD[68]。总的来说,NTRK融合患者的脑转移似乎不太常见,只有约5%的接受拉罗曲尼临床试验的患者发生脑转移[69]。在这些患者中,67%(4/6名患者)为非小细胞肺癌,针对他们,拉罗替尼表现出良好的临床活性,颅内有效率为60%[69]。类似地,恩曲替尼是一种可作为替代选择的的第一代TRK抑制剂,具有抗ALK和ROS1阳性肿瘤的活性,其ORR为57%,平均OS为20.9个月,此数据来源于一项对54例NTRK融合患者的汇总分析[70]。基于这些结果,FDA最近批准对NTRK阳性肿瘤患者使用恩曲替尼[50]。

在先前接受过拉罗替尼和恩曲替尼治疗的患者中,发现了TRK激酶结构域内的多种获得性耐药突变。导致耐药的最常见的氨基酸替换往往发生在NTRK1融合中的G595R(和NTRK3融合中的G623R)的激酶结构域的solvent front区域,这些突变(以及F589L、G667S、G696A位置的其他突变)直接干扰药物结合,是下一代TRK抑制剂的关键靶点,例如目前正在临床试验中的洛普替尼(Repotrectinib)和塞利曲替尼(Selitrectinib)[67,71-73]。总的来说,TRK抑制剂具有良好的耐受性,但其独特的毒性似乎与对神经系统的靶向效应有关(包括头晕、感觉异常和认知障碍以及贫血和肝炎)[65,67]。

EGFR和HER2 20外显子插入

EGFR和HER2都是HER家族酪氨酸激酶受体的成员,在这两种情况下,结构类似的20外显子插入突变可导致组成性激酶激活和下游信号转导。此外,HER2可以与其他HER受体形成异源二聚体,诱导EGFR转磷酸化。总之,这些突变约占肺腺癌的4%,其生物学特性与传统的EGFR和HER2突变有所不同,因此对目前可用的靶向治疗无效[74,75]。这主要是由于20外显子插入诱导形成的药物结合袋较小,在空间上阻碍了现有EGFR抑制剂的结合[75]。在非小细胞肺癌中,HER2激活突变几乎完全是由于20外显子第775密码子处4个氨基酸(YVMA)的重复或插入所致[74,76-78]。另一方面,经典的敏感性EGFR突变占所有EGFR突变病例的85%~90%,但EGFR20外显子插入突变仅占所有EGFR突变病例的10%,并且与对第一代EGFR抑制剂的初始耐药相关,与敏感性EGFR突变相比,其预后亦较差[79]。并且,临床试验表明,应用曲妥珠单抗(Trastuzumab)或奈拉替尼(Neratinib)、拉帕替尼(Lapatinib)和阿法替尼等TKIs靶向HER2过表达的策略对肺癌无效,有效率<10%[80,81]。当时,HER2的过表达是通过免疫组织化学(Immunohistochemistry,IHC)检测蛋白质水平而确定的,与乳腺癌不同,对于肺癌而言,HER2的过表达不是HER2靶向治疗有效的良好预测因子[78]。随着DNA测序变得越来越广泛,它允许识别新的生物标记物,如EGFR或HER2中的20外显子插入突变,这些突变可以预测曲妥珠单抗-美坦新偶联物(Ado-trastuzumab emtansine,TDM-1)[78]以及下一代泛HER/EGFR超家族TKIs的获益情况。

一些新的有希望的靶向疗法包括波齐替尼(Poziotinib)、TAK-788、吡咯替尼(Pyrotinib)和JNJ-372,以及其他具有临床前活性的药物,如塔洛替尼(Tarloxotinib)、鲁米尼替尼(Luminespib)、TAS6417和复合物1A[82]。在这些新药物中,作为pan-HER/EGFR-TKIs,波齐替尼、TAK-788和吡咯替尼是临床开发进展最快的药物。Ⅱ期试验的早期结果表明,将每日16 mg的波齐替尼予以EGFR20外显子插入患者后,其ORR为55%(24/44名患者),而予以HER2 20外显子插入患者后,其ORR为50%(6/12名患者)。然而,因发生≥3级的皮疹、腹泻或甲沟炎,以及1例发生了5级肺炎,63%的患者需要减少剂量。值得注意的是,体外小鼠模型也已证明,针对波齐替尼的获得性、耐药性可能是由HER2的C805S或EGFR的C797S中的二次点突变引起的,这种突变可以被热休克蛋白90抑制剂如芦米司匹(luminespib)克服,后者可和EGFR20外显子激酶相互作用,并导致其降解[82,84]。

同时,也对26例EGFR20外显子插入患者进行了关于TAK-788的研究,证明每天予80~160 mg的剂量可达到54%的ORR和89%的DCR(疾病控制率,Disease Control Rate),安全可耐受,最常见的不良反应包括腹泻、皮疹、口炎、恶心和疲劳[85]。在多种20外显子插入变异体中均发现有治疗反应,一个扩展队列目前正在招募更多患者。值得注意的是,TAK-788的剂量限制性毒性为肺炎,在34名患者中有2名患者被观察到这一情况[85]。基于患者来源的异种移植模型的临床前研究和对15例治疗病例的初步分析,吡咯替尼也表现得非常有前景。Ⅱ期临床推荐的吡咯替尼使用剂量为400 mg/d,ORR为53%,中位PFS为6.4个月,尚未报告3级或4级不良事件[87]。在关于直接针对EGFR和MET的双特异性抗体JNJ-372的研究中,也纳入了一组EGFR或HER2 20外显子插入的患者,发现在27名患者中有8名患者出现应答,其中一名是在使用波齐替尼治疗后有进展的患者;此外,27例患者中有14例在治疗后病情持续稳定[27]。

MET

原发性MET驱动的非小细胞肺癌

多种MET变异可导致其下游致癌性的MAPK信号传导,例如MET高水平扩增或剪接位点突变,后者导致14外显子跳跃,并随后丢失MET蛋白上的CBL E3泛素连接酶结合位点。从而减弱降解蛋氨酸蛋白的能力,使细胞更依赖于下游蛋氨酸信号通路[88,89]。MET第14外显子跳跃突变发生于3%~4%的NSCLC中[89,90],并可应用基于组织或血液DNA的NGS检测到,尽管在组织样本中检测到MET变异的患者,但基于血液的测序可能仅检测到一半阳性[91]。即使使用基于组织的DNA检测,我们也可能低估了由于MET基因内的大范围非编码区(通常未充分测序)而导致MET第14外显子跳跃突变的患者数量;为了克服这一问题,针对初始在基于组织DNA的NGS检测为阴性的患者使用RNA测序,可以在额外2%~3%的病例中检测到MET第14外显子跳跃突变[92]。

一旦发现MET高水平扩增或14外显子跳跃突变,目前可用的靶向治疗包括克唑替尼或卡博替尼(Cabozantinib)。这两种多激酶抑制剂已被FDA批准用于其他情况,亦已被少数病例系列或早期临床试验证明其具有一定程度的MET抑制剂活性。克唑替尼是研究最充分的MET-TKI,作为正在进行的PROFILE 1001研究的一部分,治疗了69名患者,ORR为32%,45%的患者病情稳定,中位PFS为7.3个月[91]。值得注意的是,克唑替尼被归类为Ⅰa型MET抑制剂,它通过与铰链(Y1230)和solvent front类型的甘氨酸残基(G1163)的相互作用而结合MET。反之,卡博替尼则属Ⅱ型MET抑制剂,它通过ATP腺嘌呤结合位点和疏水后囊区结合MET。临床上,克唑替尼可能是一种比卡博替尼更具特异性的MET抑制剂,具有更少的非靶向不良事件,卡博替尼则更可能具有另外的拮抗MET的能力[93]。此外,理论上,针对克唑替尼出现solvent front类型耐药突变的患者可能对卡博替尼仍能产生反应,因为它不依赖和G1163残基的相互作用[93]。

下一代选择性Ⅰb类MET抑制剂目前正在临床试验中,已显示出非常积极的效果。例如,针对28例MET第14外显子跳跃突变的初治患者,卡马替尼(Capmatinib)取得了67.9%的ORR和96.4%的DCR;在先前接受过治疗的患者中,卡马替尼的疗效较低,但仍显示ORR为40.6%,DCR为78.3%[94]。约半数CNS转移患者显示了颅内反应[94]。类似地,特泊替尼(Tepotinib)是另一种选择性MET抑制剂,其ORR范围为45%~50%,这取决于通过血液或组织来检测证实MET变异,平均DOR则持续14.3个月[95]。作为一种类效应,服用卡马替尼或特泊替尼的患者往往会出现1~2级外周水肿和胃肠道毒性,如恶心、呕吐、腹泻。

获得性MET扩增

MET的14外显子跳跃突变往往与MET高水平扩增或拷贝数增加共存,亦与更高的MET蛋白表达相关,而且,可被发现于高达20%的针对第三代EGFR抑制剂如奥希替尼产生耐药性的患者中[20,96]。值得注意的是,沃利替尼是另一种选择性的Ⅰb类MET抑制剂,它在TATTON一期试验中与奥希替尼联合使用,在ORCHARD二期试验中作为治疗组应用(患者同时具有EGFR突变和MET扩增)。初步疗效数据显示ORR为52%,平均DOR为7.1个月;在先前使用过第三代EGFR抑制剂治疗的队列中,联合治疗显示ORR为25%(48名患者中有12名),SD为44%(48名患者中有21名),包括一些CNS转移患者(97名)。

对MET抑制剂的原发性耐药可能是缺乏MET蛋白表达所致(通过免疫组化或质谱测定),尽管基于DNA的测序可证实MET变异[98]。据推测,肿瘤缺乏MET蛋白表达可能是翻译后修饰事件所致,可能不会对癌基因成瘾,因此对MET-TKIs治疗无反应[98]。针对MET抑制剂的继发性耐药机制,其特征尚不甚清楚,最常见报道的是对旁路信号通路的依赖性增加,如继发性RAS变异或EGFR/HER2扩增[98,99]。发生在激酶结构域的二次突变也可导致克唑替尼耐药,这通常发生在D1228和Y1230[98,100-102]。

RET

约2%的肺癌会发生RET变异,这可通过基于组织或血液DNA的NGS进行识别,然而,RNA测序能够识别罕见的RET融合伴侣,从而可显著提高检出率[92]。肿瘤中RET主要通过两种机制激活:RET融合和RET激活性点突变。RET融合最常见于甲状腺乳头状癌和NSCLC(70%的病例中最常见的融合伴侣为KIF5B)[103,104],而RET激活性点突变主要发生于甲状腺髓样癌。针对RET驱动的肿瘤,FDA批准的靶向疗法药物包括改变用途的具有中度活性的多激酶抑制剂,如卡博替尼、凡德他尼(Vandetanib)和舒尼替尼(Sunitinib),它们的ORR范围为18%~47%,以及病例报告推荐的尼达尼布(Nintedanib)和仑伐替尼(Lenvatinib)[103,105,106]。然而,这些多激酶抑制剂对RET没有选择性,因此患者也会产生与VEGF抑制相关的非靶向剂量限制性毒性,如高血压、出血和形成血栓。

最近,一些选择性RET抑制剂在早期试验中显示出良好的疗效和耐受毒性。在一项应用选择性RET抑制剂LOXO-292(Selpercatinib,塞尔帕替尼)的剂量递增Ⅰ期研究中,37名患者中有25名(68%)对治疗有客观反应。此外,4例CNS转移患者均达到颅内病灶PR。有4例患者出现3级不良事件,包括腹泻、肝酶升高、血小板减少和肿瘤溶解综合征[107]。另一种很有前景的RET TKI是BLU-667(Pralsetinib,普拉替尼),其对RET的选择性是VEGFR2的90倍,并且已证明其对某些卡博替尼耐药突变亦具有活性,例如V804看门残基(Gatekeeper residue)[104,108]。ARROW研究的NSCLC扩展队列(n=48)的中期结果表明,BLU-667疗效甚佳,ORR为58%,DCR为96%,9名患者中有7名出现颅内反应。DOR中位数尚未达到,部分病例随访已达2年。BLU-667的一般耐受性良好,最常见不良反应为1~2级,包括中性粒细胞减少、便秘、肝酶升高、疲劳和高血压。7%的患者可发生导致治疗中断的严重不良反应,包括肺炎、低氧血症、粘膜炎、骨髓抑制、步态障碍和贫血。在美国,BLU-667已被授予突破性治疗指定地位,应用于铂类化疗后病情进展的患者,这可能会导致更快获批。

KRAS

KRAS是NSCLC中最常见的突变的致癌性驱动因子,然而,目前尚无指南推荐针对KRAS突变患者的靶向治疗。AMG 510(Sotorasib)属第一类KRAS G12C小分子抑制剂,能不可逆地结合KRAS G12C的半胱氨酸部分,使之处于非活性状态。第一次针对实体瘤患者进行的人体研究的结果非常鼓舞人心,不良事件主要是1~2级,且没有剂量限制性毒性。在接受治疗的10名肺癌患者中,有5名患者达到了PR,另4名患者达到了SD(总体疗效最佳)。另一种KRAS G12C抑制剂是MRTX849,尽管尚未公布结果但已开始为Ⅰ期临床试验招募患者,。重要的是,这些KRAS TKIs仅对G12C突变的患者亚群具有活性,这约占晚期肺癌患者KRAS突变的44%[109]。

结论

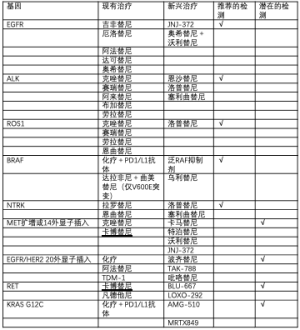

分子检测在识别驱动基因突变方面的应用和药物开发的快速发展,使得从组织和/或血液中进行多重NGS检测的需求更加迫切,以便为晚期肺癌患者确定最合适的治疗方案。目前,大多数指南建议至少检测EGFR敏感性突变、ALK融合、ROS1融合、BRAF V600E和NTRK融合,因为这些变异有FDA批准的针对性靶向疗法。此外,我们还强调了针对MET高水平扩增或14外显子跳跃突变、EGFR或HER2 20外显子插入突变、RET融合和KRAS G12C突变的有希望的治疗性研究,这些突变也为检测这些驱动突变提供了支持(表1)。此外,多重NGS检测可能有助于识别癌基因驱动的肺癌患者,这些患者在靶向治疗后给予抗PD-1/L1检查点抑制剂,可能承担更高的严重毒性风险(如肺炎或肝炎),且缺乏获益。

Full table

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors Alfredo Addeo and Giuseppe Banna for the series “Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC)” published in Precision Cancer Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/pcm.2019.11.03). The series “Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC)” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. Sandip Pravin Patel receives scientific advisory income from: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Illumina, Nektar, Novartis, Tempus. Sandip Pravin Patel’s university receives research funding from: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Fate, Incyte, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Merck, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, Xcovery. Fate Therapeutics, Genocea, Iovance. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, et al. Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. JAMA ;2014:1998-2006. [PubMed]

- Barlesi F, Mazieres J, Merlio JP, et al. Routine molecular profiling of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a 1-year nationwide programme of the French Cooperative Thoracic Intergroup (IFCT). Lancet 2016;387:1415-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Beasley MB, et al. Molecular testing guideline for selection of lung cancer patients for EGFR and ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:823-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsao AS, Scagliotti GV, Bunn PA Jr, et al. Scientific Advances in Lung Cancer 2015. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:613-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rotow J, Bivona TG. Understanding and targeting resistance mechanisms in NSCLC. Nat Rev Cancer 2017;17:637-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Aisner DL, et al. Updated Molecular Testing Guideline for the Selection of Lung Cancer Patients for Treatment With Targeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: Guideline From the College of American Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:323-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pennell NA, Mutebi A, Zhou ZY, et al. Economic Impact of Next-Generation Sequencing Versus Single-Gene Testing to Detect Genomic Alterations in Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Using a Decision Analytic Model. JCO Precis Oncol 2019. doi:

10.1200/PO.18.00356 . - Oxnard GR, Arcila ME, Sima CS, et al. Acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR-mutant lung cancer: distinct natural history of patients with tumors harboring the T790M mutation. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:1616-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu HA, Arcila ME, Rekhtman N, et al. Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:2240-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mok TS, Wu YL, Ahn MJ, et al. Osimertinib or Platinum-Pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-Positive Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;376:629-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tagrisso significantly improves overall survival in the Phase III FLAURA trial for 1st-line EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Aug 19]. Available online: https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2019/tagrisso-significantly-improves-overall-survival-in-the-phase-iii-flaura-trial-for-1st-line-egfr-mutated-non-small-cell-lung-cancer-09082019.html

- Planchard D, Boyer MJ, Lee JS, et al. Postprogression Outcomes for Osimertinib versus Standard-of-Care EGFR-TKI in Patients with Previously Untreated EGFR-mutated Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:2058-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamada T, Hirai S, Katayama Y, et al. Retrospective efficacy analysis of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Med [Internet]. 2019 Feb 21. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/

10.1002/cam4.2037 - Zhang T, Wan B, Zhao Y, et al. Treatment of uncommon EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: new evidence and treatment. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2019;8:302-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brindel A, Althakfi W, Barritault M, et al. Uncommon EGFR mutations in lung adenocarcinomas: clinical features and response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. OncologyPRO. 2018 Oct 19 [cited 2019 Aug 12]. Available online: https://oncologypro.esmo.org/Meeting-Resources/ESMO-2018-Congress/Uncommon-EGFR-mutations-in-lung-adenocarcinomas-clinical-features-and-response-to-tyrosine-kinase-inhibitors

- Janne PA, Yu HA, Johnson ML, et al. Safety and preliminary antitumor activity of U3-1402: A HER3-targeted antibody drug conjugate in EGFR TKI-resistant, EGFRm NSCLC. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:abstr 9010.

- Brown BP, Zhang YK, Westover D, et al. On-target resistance to the mutant-selective EGFR inhibitor osimertinib can develop in an allele specific manner dependent on the original EGFR activating mutation. Clin Cancer Res 2019; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fassunke J, Müller F, Keul M, et al. Overcoming EGFRG724S-mediated osimertinib resistance through unique binding characteristics of second-generation EGFR inhibitors. Nat Commun 2018;9:4655. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oxnard GR, Hu Y, Mileham KF, et al. Assessment of Resistance Mechanisms and Clinical Implications in Patients With EGFR T790M-Positive Lung Cancer and Acquired Resistance to Osimertinib. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:1527-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam SS, Cheng Y, Zhou C, et al. LBA50 Mechanisms of acquired resistance to first-line osimertinib: Preliminary data from the phase III FLAURA study. Ann Oncol 2018;29:mdy424.063.

- Noronha V, Joshi A, Patil VM, et al. Phase III randomized trial comparing gefitinib to gefitinib with pemetrexed-carboplatin chemotherapy in patients with advanced untreated EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer (gef vs gef+C). J Clin Oncol 2019;37:abstr 9001.

- Nakagawa K, Garon EB, Seto T, et al. RELAY: A multinational, double-blind, randomized Phase 3 study of erlotinib (ERL) in combination with ramucirumab (RAM) or placebo (PL) in previously untreated patients with epidermal growth factor receptor mutation-positive (EGFRm) metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol 2019;37:abstr 9000.

- New data on mechanisms of acquired resistance after 1st-line Tagrisso in NSCLC support initiation of ORCHARD trial to explore post-progression treatment options [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 May 15]. Available online: https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2018/new-data-on-mechanisms-of-acquired-resistance-after-1st-line-tagrisso-in-nsclc-support-initiation-of-orchard-trial-to-explore-post-progression-treatment-options-19102018.html

- Nishino M, Suda K, Kobayashi Y, et al. Effects of secondary EGFR mutations on resistance against upfront osimertinib in cells with EGFR-activating mutations in vitro. Lung Cancer 2018;126:149-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang Z, Yang N, Ou Q, et al. Investigating Novel Resistance Mechanisms to Third-Generation EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Osimertinib in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:3097-107. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Li Y, Ou Q, et al. Acquired EGFR L718V mutation mediates resistance to osimertinib in non-small cell lung cancer but retains sensitivity to afatinib. Lung Cancer 2018;118:1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haura EB, Cho BC, Lee JS, et al. JNJ-61186372 (JNJ-372), an EGFR-cMet bispecific antibody, in EGFR-driven advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol 2019;37:abstr 9009.

- Sequist LV, Lee JS, Han JY, et al. TATTON Phase Ib expansion cohort: Osimertinib plus savolitinib for patients (pts) with EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified NSCLC after progression on prior third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI). Cancer Res 2019;79:abstr CT033.

- Piotrowska Z, Isozaki H, Lennerz JK, et al. Landscape of Acquired Resistance to Osimertinib in EGFR-Mutant NSCLC and Clinical Validation of Combined EGFR and RET Inhibition with Osimertinib and BLU-667 for Acquired RET Fusion. Cancer Discov 2018;8:1529-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jia Y, Yun CH, Park E, et al. Overcoming EGFR(T790M) and EGFR(C797S) resistance with mutant-selective allosteric inhibitors. Nature 2016;534:129-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- To C, Jang J, Chen T, et al. Single and Dual Targeting of Mutant EGFR with an Allosteric Inhibitor. Cancer Discov 2019;9:926-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vojnic M, Kubota D, Kurzatkowski C, et al. Acquired BRAF Rearrangements Induce Secondary Resistance to EGFR therapy in EGFR-Mutated Lung Cancers. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:802-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ho CC, Liao WY, Lin CA, et al. Acquired BRAF V600E Mutation as Resistant Mechanism after Treatment with Osimertinib. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:567-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solassol J, Vendrell JA, Senal R, et al. Challenging BRAF/EGFR co-inhibition in NSCLC using sequential liquid biopsies. Lung Cancer 2019;133:45-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin JJ, Riely GJ, Shaw AT. Targeting ALK: Precision Medicine Takes on Drug Resistance. Cancer Discov 2017;7:137-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2167-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho BC, Kim DW, Bearz A, et al. ASCEND-8: A Randomized Phase 1 Study of Ceritinib, 450 mg or 600 mg, Taken with a Low-Fat Meal versus 750 mg in Fasted State in Patients with Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK)-Rearranged Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:1357-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, et al. Alectinib versus Crizotinib in Untreated ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:829-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gadgeel S, Peters S, Mok T, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in treatment-naive anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive (ALK+) non-small-cell lung cancer: CNS efficacy results from the ALEX study. Ann Oncol 2018;29:2214-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, et al. Brigatinib versus Crizotinib in ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2027-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gainor JF, Dardaei L, Yoda S, et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance to First- and Second-Generation ALK Inhibitors in ALK-Rearranged Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov 2016;6:1118-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoda S, Lin JJ, Lawrence MS, et al. Sequential ALK Inhibitors Can Select for Lorlatinib-Resistant Compound ALK Mutations in ALK-Positive Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov 2018;8:714-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaw AT, Solomon BJ, Besse B, et al. ALK Resistance Mutations and Efficacy of Lorlatinib in Advanced Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:1370-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, et al. Lorlatinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a global phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:1654-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ou S-HI, Zhu VW. CNS metastasis in ROS1+ NSCLC: An urgent call to action, to understand, and to overcome. Lung Cancer 2019;130:201-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bergethon K, Shaw AT, Ou SH, et al. ROS1 rearrangements define a unique molecular class of lung cancers. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:863-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaw AT, Riely GJ, Bang YJ, et al. Crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): updated results, including overall survival, from PROFILE 1001. Ann Oncol 2019;30:1121-6. [Crossref]

- Shaw AT, Ou SH, Bang YJ, et al. Crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1963-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lim SM, Kim HR, Lee JS, et al. Open-Label, Multicenter, Phase II Study of Ceritinib in Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring ROS1 Rearrangement. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2613-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Center for Drug Evaluation, Research. FDA approves entrectinib for NTRK solid tumors and ROS-1 NSCLC [Internet]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2019 [cited 2019 Aug 19]. Available online: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-entrectinib-ntrk-solid-tumors-and-ros-1-nsclc

- Drilon A, Siena S, Ou SI, et al. Safety and Antitumor Activity of the Multitargeted Pan-TRK, ROS1, and ALK Inhibitor Entrectinib: Combined Results from Two Phase I Trials (ALKA-372-001 and STARTRK-1). Cancer Discov 2017;7:400-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gainor JF, Tseng D, Yoda S, et al. Patterns of Metastatic Spread and Mechanisms of Resistance to Crizotinib in ROS1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 2017. doi:

10.1200/PO.17.00063 . - Solomon BJ, Martini J, Ou SI, et al. Efficacy of lorlatinib in patients (pts) with ROS1-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and ROS1 kinase domain mutations. Ann Oncol 2018;29:viii493-547.

- Ou S, Shaw A, Riely G, et al. OA02.03 Clinical Activity of Lorlatinib in Patients with ROS1+ Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Phase 2 Study Cohort EXP-6. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:S322-3. [Crossref]

- Marchetti A, Felicioni L, Malatesta S, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3574-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Planchard D, Smit EF, Groen HJM, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously untreated BRAFV600E-mutant metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1307-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Planchard D, Besse B, Groen HJM, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously treated BRAF(V600E)-mutant metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: an open-label, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:984-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Planchard D, Besse B, Kim TM, et al. Updated survival of patients (pts) with previously treated BRAF V600E–mutant advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who received dabrafenib (D) or D + trametinib (T) in the phase II BRF113928 study. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:abstr 9075.

- Davies MA, Saiag P, Robert C, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAFV600-mutant melanoma brain metastases (COMBI-MB): a multicentre, multicohort, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:863-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mazières J, Drilon A, Lusque A, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry. Ann Oncol 2019;30:1321-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dagogo-Jack I, Martinez P, Yeap BY, et al. Impact of BRAF Mutation Class on Disease Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes in BRAF-mutant Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:158-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dudnik E, Peled N, Nechushtan H, et al. BRAF Mutant Lung Cancer: Programmed Death Ligand 1 Expression, Tumor Mutational Burden, Microsatellite Instability Status, and Response to Immune Check-Point Inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:1128-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leonetti A, Facchinetti F, Rossi G, et al. BRAF in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Pickaxing another brick in the wall. Cancer Treat Rev 2018;66:82-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sullivan RJ, Infante JR, Janku F, et al. First-in-Class ERK1/2 Inhibitor Ulixertinib (BVD-523) in Patients with MAPK Mutant Advanced Solid Tumors: Results of a Phase I Dose-Escalation and Expansion Study. Cancer Discov 2018;8:184-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cocco E, Scaltriti M, Drilon A. NTRK fusion-positive cancers and TRK inhibitor therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018;15:731-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Benayed R, Offin MD, Mullaney KA, et al. Comprehensive detection of targetable fusions in lung adenocarcinomas by complementary targeted DNAseq and RNAseq assays. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:abstr 12076.

- Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, et al. Efficacy of Larotrectinib in TRK Fusion-Positive Cancers in Adults and Children. N Engl J Med 2018;378:731-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hong DS, Kummar S, Farago AF, et al. Larotrectinib efficacy and safety in adult TRK fusion cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:abstr 3122.

- Drilon AE, DuBois SG, Farago AF, et al. Activity of larotrectinib in TRK fusion cancer patients with brain metastases or primary central nervous system tumors. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:abstr 2006.

- Demetri GD, Paz-Ares L, Farago AF, et al. Efficacy and safety of entrectinib in patients with NTRK fusion-positive (NTRK-fp) Tumors: Pooled analysis of STARTRK-2, STARTRK-1 and ALKA-372-001. Ann Oncol 2018;29:abstr LBA17.

- Drilon A, Nagasubramanian R, Blake JF, et al. A Next-Generation TRK Kinase Inhibitor Overcomes Acquired Resistance to Prior TRK Kinase Inhibition in Patients with TRK Fusion-Positive Solid Tumors. Cancer Discov 2017;7:963-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drilon A, Ou SI, Cho BC, et al. Repotrectinib (TPX-0005) Is a Next-Generation ROS1/TRK/ALK Inhibitor That Potently Inhibits ROS1/TRK/ALK Solvent- Front Mutations. Cancer Discov 2018;8:1227-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- AACR 2019: Phase I Trial Evaluates LOXO-195 in Patients With NTRK-Positive Solid Tumors - The ASCO Post [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 17]. Available online: https://www.ascopost.com/News/59906

- Pillai RN, Behera M, Berry LD, Rossi MR, Kris MG, Johnson BE, et al. HER2 mutations in lung adenocarcinomas: A report from the Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium. Cancer 2017;123:4099-105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robichaux JP, Elamin YY, Tan Z, et al. Mechanisms and clinical activity of an EGFR and HER2 exon 20-selective kinase inhibitor in non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Med 2018;24:638-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arcila ME, Chaft JE, Nafa K, et al. Prevalence, clinicopathologic associations, and molecular spectrum of ERBB2 (HER2) tyrosine kinase mutations in lung adenocarcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:4910-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kosaka T, Tanizaki J, Paranal RM, et al. Response Heterogeneity of EGFR and HER2 Exon 20 Insertions to Covalent EGFR and HER2 Inhibitors. Cancer Res 2017;77:2712-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li BT, Shen R, Buonocore D, et al. Ado-Trastuzumab Emtansine for Patients With HER2-Mutant Lung Cancers: Results From a Phase II Basket Trial. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2532-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yasuda H, Park E, Yun CH, et al. Structural, biochemical, and clinical characterization of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 20 insertion mutations in lung cancer. Sci Transl Med 2013;5:216ra177. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clamon G, Herndon J, Kern J, et al. Lack of trastuzumab activity in nonsmall cell lung carcinoma with overexpression of erb-B2: 39810: a phase II trial of Cancer and Leukemia Group B. Cancer 2005;103:1670-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mazières J, Barlesi F, Filleron T, et al. Lung cancer patients with HER2 mutations treated with chemotherapy and HER2-targeted drugs: results from the European EUHER2 cohort. Ann Oncol 2016;27:281-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vyse S, Huang PH. Targeting EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2019;4:5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heymach J, Negrao M, Robichaux J, et al. OA02.06 A Phase II Trial of Poziotinib in EGFR and HER2 exon 20 Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:S323-4. [Crossref]

- Koga T, Kobayashi Y, Tomizawa K, et al. Activity of a novel HER2 inhibitor, poziotinib, for HER2 exon 20 mutations in lung cancer and mechanism of acquired resistance: An in vitro study. Lung Cancer 2018;126:72-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Janne PA, Neal JW, Camidge DR, et al. Antitumor activity of TAK-788 in NSCLC with EGFR exon 20 insertions. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:abstr 9007.

- Doebele RC, Riely GJ, Spira AI, et al. First report of safety, PK, and preliminary antitumor activity of the oral EGFR/HER2 exon 20 inhibitor TAK-788 (AP32788) in non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol 2018;36:abstr 9015.

- Wang Y, Jiang T, Qin Z, et al. HER2 exon 20 insertions in non-small-cell lung cancer are sensitive to the irreversible pan-HER receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor pyrotinib. Ann Oncol 2019;30:447-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drilon A. MET Exon 14 Alterations in Lung Cancer: Exon Skipping Extends Half-Life. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:2832-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paik PK, Drilon A, Fan PD, et al. Response to MET inhibitors in patients with stage IV lung adenocarcinomas harboring MET mutations causing exon 14 skipping. Cancer Discov 2015;5:842-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Awad MM, Oxnard GR, Jackman DM, et al. MET Exon 14 Mutations in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Are Associated With Advanced Age and Stage-Dependent MET Genomic Amplification and c-Met Overexpression. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:721-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drilon A, Clark J, Weiss J, et al. OA12.02 Updated Antitumor Activity of Crizotinib in Patients with MET Exon 14-Altered Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:S348. [Crossref]

- Benayed R, Offin M, Mullaney K, et al. High yield of RNA sequencing for targetable kinase fusions in lung adenocarcinomas with no driver alteration detected by DNA sequencing and low tumor mutation burden. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:4712-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reungwetwattana T, Liang Y, Zhu V, et al. The race to target MET exon 14 skipping alterations in non-small cell lung cancer: The Why, the How, the Who, the Unknown, and the Inevitable. Lung Cancer 2017;103:27-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wolf J, Seto T, Han JY, et al. Capmatinib (INC280) in METΔex14-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Efficacy data from the phase II GEOMETRY mono-1 study. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:abstr 9004.

- Paik PK, Veillon R, Cortot AB, et al. Phase II study of tepotinib in NSCLC patients with METex14 mutations. | 2019 ASCO Annual Meeting Abstracts. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:abstr 9005.

- Tong JH, Yeung SF, Chan AWH, et al. MET Amplification and Exon 14 Splice Site Mutation Define Unique Molecular Subgroups of Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma with Poor Prognosis. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:3048-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu H, Ahn MJ, Kim SW, et al. CT032 - TATTON Phase Ib expansion cohort: Osimertinib plus savolitinib for patients (pts) with EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified NSCLC after progression on prior first/second-generation epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) [abstract]. Proceedings of the 110th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research [Internet]. 2019. Available online: https://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/#!/6812/presentation/9826

- Guo R, Offin M, Brannon AR, et al. MET inhibitor resistance in patients with MET exon 14-altered lung cancers. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:abstr 9006.

- Ding G, Wang J, Ding P, et al. Case report: HER2 amplification as a resistance mechanism to crizotinib in NSCLC with MET exon 14 skipping. Cancer Biol Ther 2019;20:837-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ou SI, Young L, Schrock AB, et al. Emergence of Preexisting MET Y1230C Mutation as a Resistance Mechanism to Crizotinib in NSCLC with MET Exon 14 Skipping. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:137-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heist RS, Sequist LV, Borger D, et al. Acquired Resistance to Crizotinib in NSCLC with MET Exon 14 Skipping. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1242-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bahcall M, Sim T, Paweletz CP, et al. Acquired METD1228V Mutation and Resistance to MET Inhibition in Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov 2016;6:1334-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gautschi O, Milia J, Filleron T, et al. Targeting RET in Patients With RET-Rearranged Lung Cancers: Results From the Global, Multicenter RET Registry. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:1403-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gainor JF, Lee DH, Curigliano G, et al. Clinical activity and tolerability of BLU-667, a highly potent and selective RET inhibitor, in patients (pts) with advanced RET-fusion+ non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol 2019;37:abstr 9008.

- Lee SH, Lee JK, Ahn MJ, et al. Vandetanib in pretreated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer-harboring RET rearrangement: a phase II clinical trial. Ann Oncol 2017;28:292-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoh K, Seto T, Satouchi M, et al. Vandetanib in patients with previously treated RET-rearranged advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (LURET): an open-label, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2017;5:42-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oxnard G, Subbiah V, Park K, et al. OA12.07 Clinical Activity of LOXO-292, a Highly Selective RET Inhibitor, in Patients with RET Fusion+ Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:S349-50. [Crossref]

- Subbiah V, Gainor JF, Rahal R, et al. Precision Targeted Therapy with BLU-667 for RET-Driven Cancers. Cancer Discov 2018;8:836-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arbour KC, Jordan E, Kim HR, et al. Effects of Co-occurring Genomic Alterations on Outcomes in Patients with KRAS-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:334-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

卓文磊

陆军军医大学第二附属医院肿瘤科副主任、副教授、副主任医师、硕导,国家公派留美博士后。主要从事肿瘤靶向治疗耐药的相关研究。担任中国抗癌协会肿瘤营养专委会委员等学术职务。主持国家自然科学基金课题2项,以第一(通讯)作者发表SCI论文30余篇,F1000收录1篇。参编《肿瘤免疫营养治疗指南》、《肿瘤恶液质临床诊断与治疗指南》等临床指南。参编《肿瘤免疫营养》等专著。参译《运动肿瘤学》、《生物医学研究报告指南:用户手册》、中文版《UptoDate》临床顾问数据库等。以第一发明人获批国家发明专利一项,获评第三批重庆市学术技术带头人后备人选。(更新时间:2021/8/6)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Vu P, Patel SP. Non-small cell lung cancer targetable mutations: present and future. Precis Cancer Med 2020;3:5.