实体器官移植后的癌症诊断:我们需要知道来源细胞吗?

前言

细胞和实体器官移植(SOT)取得了空前成功。随着移植病例数量的增加和移植受者生存率的提高,这一人群的恶性肿瘤发生率呈上升趋势。恶性肿瘤是继心血管疾病和感染性疾病之后的第三大SOT死亡原因[1]。由于供体和受体因素以及免疫抑制的结合,SOT患者的癌症成为一个特殊的挑战。在SOT手术中,肺移植(LTx)是第四种最常进行的手术,在过去二十年中,肺移植从一种预后差、风险高的手术转变为一种成熟有效、能够治疗过去无法治愈肺部疾病的方法,患者接受移植后中位总生存期超过5年[2,3]。供者选择的标准在各机构中并不统一,许多移植项目允许长期吸烟的人作为供者,以增加供者器官的可用性[4]。随着越来越多的SOT患者被诊断为新的恶性肿瘤,确定癌症是起源于受体器官还是来源于供体器官对于进一步界定供体选择标准、患者咨询、通知其他接受者以及可能的治疗选择具有重要意义。

病例报道

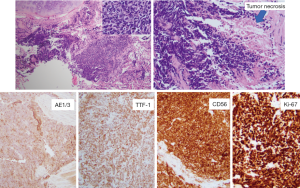

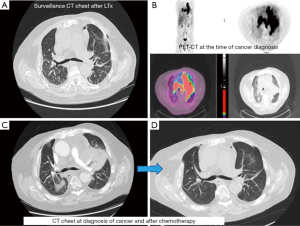

70岁男性,有20包年吸烟史,患有特发性肺纤维化超过5年。2018年春,他接受了一位吸烟史不明的捐赠者的双肺移植。LTx后不久,他的生活质量有了显著改善,不额外吸氧就能够长距离行走。他与肺移植团队密切随访,并在LTx术后6个月进行计算机断层扫描(CT)和支气管镜检查(图1)。这两项测试结果都无异常,没有显示排斥反应的迹象,也没有发现恶性肿瘤的迹象。他一直感受良好,直到同年12月,他开始出现劳力后呼吸困难伴左肩疼痛。胸部X光检查对比前后并没有发现任何新的变化,之后患者接受了非典型肺炎的经验性治疗。由于症状没有改善,他3周后再次接受了胸部CT检查,发现了一个新的左上叶肿块。进一步做正电子发射断层扫描(PET)-CT(图1)和支气管镜检查后,患者被诊断为广泛期小细胞肺癌(图2)。患者接受卡铂和依托泊苷治疗,症状和放射学反应良好(图1)。尽管抗PD-L1单克隆抗体阿替唑珠单抗在患者被诊断为小细胞肺癌时获批,但由于使用免疫检查点抑制剂治疗的患者出现高移植排斥反应,因此决定不将其纳入其治疗方案[5]。截至2019年夏末,患者均表现良好,治疗效果满意。

我们试图确定患者的小细胞肺癌是起源于供体肺还是来源于受体气道上皮细胞,结果证实为前者。这是通过使用一组12个分子标记的基因组合来完成的,这些基于PCR技术的分子标记能够识别人类DNA的高度可变区域,比较诊断为小细胞癌标本中的DNA提取物、移植肺组织以及供体正常(非恶性)肺组织。结果表明,检测到的12个小细胞癌标记物与来自供体非恶性组织碎片的12个标记物完全匹配。相反,在肿瘤组织碎片12个标记物中,和移植受体肺组织匹配的只有1个。这说明恶性肿瘤来源于供体,我们把这一消息也告知了其他接受同一供体器官的移植中心。

讨论

分子印记的基本原理

据推测,随着接受实体器官移植者数量的增加,这一人群中的癌症病例数量也将迅速增加,有几个原因可以预期这一点。首先,由于移植后照看条件的改善,这些患者的期望寿命延长,造成癌症的累积风险增加。其次,天然器官和供体器官都会受到免疫抑制药物的影响,这些药物对防止移植物排斥反应至关重要,但同样会削弱受体的抗肿瘤反应并促进潜在的致癌病毒感染[6]。最后,器官捐赠者和接受者都可能接触过烟草、烟雾和环境毒素等公认的致癌物[7]。随着越来越多的患者出现在等待“救命手术”的名单上,许多机构放宽了对捐赠者选择标准,以求解决器官者短缺的问题。英国最近发布的一份单一机构报告显示,高达47%的捐赠者有吸烟史。然而,作者声称供体吸烟史实际上并不影响LTx后的短期和中期结果[4]。其他回顾性研究与英国报告相矛盾的是,研究者不仅考虑了短期结果,还考虑了长期随访结果,发现供体吸烟可能会对受体生存期产生不利影响[8,9]。

当我们知道移植后新诊断的癌症是起源于原发器官还是移植器官,将有助于通过提高供体选择标准,把SOT患者未来出现类似问题的风险降至最低。不过即使在双肺移植的情况下,也不应认为癌症仅起源于供体细胞,也可能会来源于LTx后持续数年存在的上皮细胞嵌合体以及手术残留的气管、支气管组织等[10]。只有当SOT和癌症诊断之间的时间跨度很短,并且检测证实肿瘤细胞来源于供体,才可以说恶性肿瘤先前已经存在于供体中,并传播给受体。另外,如果SOT和诊断之间的时间间隔长达几年,并且分子检测表明是供体来源,则癌症可能在长期免疫抑制以及供体和受体的危险因素作用下原位产生[1]。

分子技术

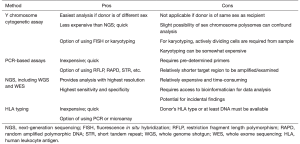

目前存在多种可用于此类分子病理学调查的技术。在已知捐赠者性别且与受体不同的情况下,利用Y染色体的荧光原位杂交(FISH)很容易进行检测[11,12]。同样,Y染色体也可以通过经典细胞遗传学进行分析[13]。在供体性别相同的情况下,可通过肿瘤细胞人白细胞抗原(HLA)单倍型分析获得有关来源细胞的信息,该单倍型分析涉及将肿瘤细胞表面的各种HLA同型与供体和受体细胞进行同型比较[14]。最后,可以对提取的DNA进行基于PCR或基于基因测序的分子遗传分析,并在肿瘤和完整受体组织之间寻找不同的等位基因模式[15]。表1总结了当前可用和适用的分子印记检测。在本病例中,样本被送到梅奥诊所实验室对12个识别人类DNA高度可变区域的标记进行了基于PCR的检测。

Full table

测试的含义

上述提到的技术可提供关于SOT后癌症的细胞起源有价值的信息,可为将来的供体选择和最大程度降低SOT后癌症发生率提供指导。患者咨询和保证也可能是上述技术一个重要应用,因为SOT等待名单上的许多患者都是没有恶性肿瘤风险的年轻人。如果他们知道SOT后会患上癌症一定大为震撼,并希望了解癌症起源。媒体曾批判一些经证实由器官捐赠者传播癌症的案例,甚至提交了法律诉讼[16-18]。另外,如果患者了解到癌症发生在自身器官,并且可能与吸烟等不良生活习惯有关,他们可能会重新考虑自己的生活方式,进而改善预后。一项对肾移植后受体患肾癌的系统综述中报道,受者和供体来源的恶性肿瘤发生率相当[19]。这篇综述认为恶性肿瘤可能是由于来源于供体和受体细胞持续的微嵌合体。当出现器官捐赠者导致的癌症时,来自同一捐赠者的其他实体器官受体需要更密切地监测随访和咨询患病可能性,以便于更早期地诊断癌症[20]。确定起源细胞也可能在免疫抑制中发挥重要作用。目前的做法是减少免疫抑制,尽早恢复免疫功能以防恶变[21]。然而,在一些供体来源的癌症病例中,停用免疫抑制药物,随后切除排斥的移植物,可使癌症得到完全治愈[20,22]。尽管使用免疫抑制剂的SOT患者接受常规化疗具有较高的感染并发症风险,但通常不影响化疗的剂量或疗程。相反,SOT患者接受免疫治疗具有很大的移植物排斥风险。如果移植排斥反应可能显著影响预后,通常应避免接受免疫治疗[5]。

关键点

观察到SOT后恶性肿瘤的发病率增加;

可以使用几种方法确定SOT患者的肿瘤起源细胞;

有关癌细胞来源的信息对于未来改进供体选择、患者和其他接受者咨询以及治疗选择可能很重要。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Precision Cancer Medicine for the series “Precision Oncology Tumor Board”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/pcm.2019.09.06). The Series “Precision Oncology Tumor Board” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. BH serves the unpaid Guest Editor of the series and as an unpaid editorial board member of Precision Cancer Medicine from Apr 2019 to Mar 2021. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Chapman JR, Webster AC, Wong G. Cancer in the transplant recipient. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2013; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- UNOS data on transplant trends: 2018 transplants by organ type. Available online: https://unos.org/data/transplant-trends. Accessed on August 21th, 2019.

- Yusen RD, Edwards LB, Dipchand AI, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-third Adult Lung and Heart-Lung Transplant Report-2016; Focus Theme: Primary Diagnostic Indications for Transplant. J Heart Lung Transplant 2016;35:1170-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sabashnikov A, Patil NP, Popov AF, et al. Long-term results after lung transplantation using organs from circulatory death donors: a propensity score-matched analysis†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:46-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Wahab N, Safa H, Abudayyeh A, et al. Checkpoint inhibitor therapy for cancer in solid organ transplantation recipients: an institutional experience and a systematic review of the literature. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:106. Erratum in: J Immunother Cancer 2019 Jun 24;7(1):158. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Geissler EK. Post-transplantation malignancies: here today, gone tomorrow? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015;12:705-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brand T, Haithcock B. Lung cancer and lung transplantation. Thorac Surg Clin 2018;28:15-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oto T, Griffiths AP, Levvey B, et al. A donor history of smoking affects early but not late outcome in lung transplantation. Transplantation 2004;78:599-606. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhorade SM, Vigneswaran W, McCabe MA, et al. Liberalization of donor criteria may expand the donor pool without adverse consequence in lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2000;19:1199-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spencer H, Rampling D, Aurora P, et al. Transbronchial biopsies provide longitudinal evidence for epithelial chimerism in children following sex mismatched lung transplantation. Thorax 2005;60:60-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Michel Ortega RM, Wolff DJ, Schandl CA, et al. Urothelial carcinoma of donor origin in a kidney transplant patient. J Immunother Cancer 2016;4:63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Picard C, Grenet D, Copie-Bergman C, et al. Small-cell lung carcinoma of recipient origin after bilateral lung transplantation for cystic fibrosis. J Heart Lung Transplant 2006;25:981-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beyer EA, DeCamp MM, Smedira NG, et al. Primary adenocarcinoma in a donor lung: evaluation and surgical management. J Heart Lung Transplant 2003;22:1174-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Boehmer L, Draenert A, Jungraithmayr W, et al. Immunosuppression and lung cancer of donor origin after bilateral lung transplantation. Lung Cancer 2012;76:118-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Soyza AG, Dark JH, Parums DV, et al. Donor-acquired small cell lung cancer following pulmonary transplantation. Chest 2001;120:1030-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- BBC News. Cystic fibrosis woman died with smoker’s donor lung. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-essex-20762437. Accessed on August 18th, 2019.

- New York Post. NYU wins kidney transplant cancer suit. Available online: https://nypost.com/2010/05/28/nyu-wins-kidney-transplant-cancer-suit. Accessed on August 18th, 2019.

- LiveScience.com. Cancer spreads from organ donor to 4 people in “extraordinary” case. Available online: https://www.livescience.com/63596-organ-donation-transmitted-breast-cancer.html. Accessed on August 18th, 2019.

- Dhakal P, Giri S, Siwakoti K, et al. Renal Cancer in Recipients of Kidney Transplant. Rare Tumors 2017;9:6550. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palanisamy A, Persad P, Koty PP, et al. Donor-derived myeloid sarcoma in two kidney transplant recipients from a single donor. Case Rep Nephrol 2015;2015:821346. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grewal AS, Padera RF, Boukedes S, et al. Prevalence and outcome of lung cancer in lung transplant recipients. Respir Med 2015;109:427-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Champion L, Culine S, Desgranchamps F, et al. Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma in a Renal Allograft: A Sustained Complete Remission After Stimulated Rejection. Am J Transplant 2017;17:1125-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Darbinyan K, Zhu C, Scheinin S, Seethamraju H, Halmos B. Cancer diagnosis after solid organ transplantation: do we need to know the cell of origin? Precis Cancer Med 2019;2:28.